Photos and travel are a natural combo. Today, rare is the person not snapping photos around the clock. Strange as it may seem, not that long ago the opposite was true. Most Americans did not own cameras; if they did, they took black-and-white photos—of special occasions, not their latest meal. Cheap cameras boomed in the 1960s, when the Polaroid Instamatic began producing color prints speedily. Before then, many travelers relied on postcards to capture scenes from their journeys.

Postcards have been around for 150 years, peaking in popularity in mid-20th century. From monotone illustrations to color pictures, they so often depict idyllic scenes that “postcard” has become equated with “picturesque”: a postcard-perfect village. They thrived before everyone and their dog had a camera-equipped smartphone. But these modest three-by-five-inch objects, now symbols of slow travel, are not obsolete souvenirs.

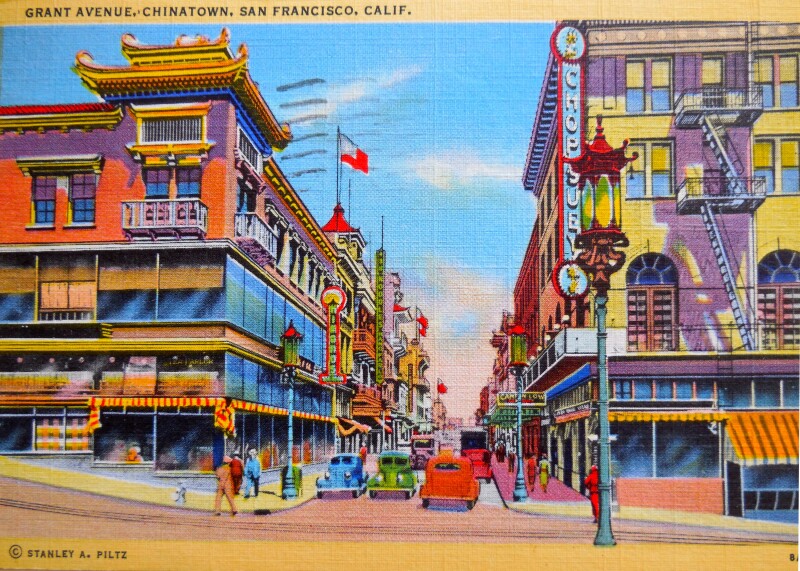

The cars depicted are one clue to the age of this postcard from San Francisco.

Photo courtesy of Pat Tompkins

A keepsake you’ll really want to keep

The word tacky seems to pair automatically with souvenir, which means a way to remember. Postcards are cheap (and some are tacky) but they are also tactile, unlike ephemeral internet posts. They remain splendid souvenirs.

Over decades, I have purchased cards at almost every museum or historic building I’ve visited. I’ve never had trouble fitting a few more into my suitcase. Flipping through them now is like a slide show of greatest hits—a wonderful reminder of things encountered on my trips. I’ve also saved those sent to me from foreign countries; these cards capture people from my past.

Shops selling cards generally also sell stamps, which is convenient. Stamps are part of the fun. When I was a kid, my basic stamp collection was how I discovered that foreign countries also had foreign names: Helvetia was Switzerland. Although my latest batch of cards, sent from Iceland, featured the most expensive, ugliest stamps I’ve ever used, stamps more often include information about their country, similar to coins and bills.

And instead of asking front desk clerks to mail your cards, find the local post office and DIY. You may discover an interesting historic building. And who doesn’t enjoy a tiny surprise in the mail, something beyond grocery ads, charity solicitations, and bills?

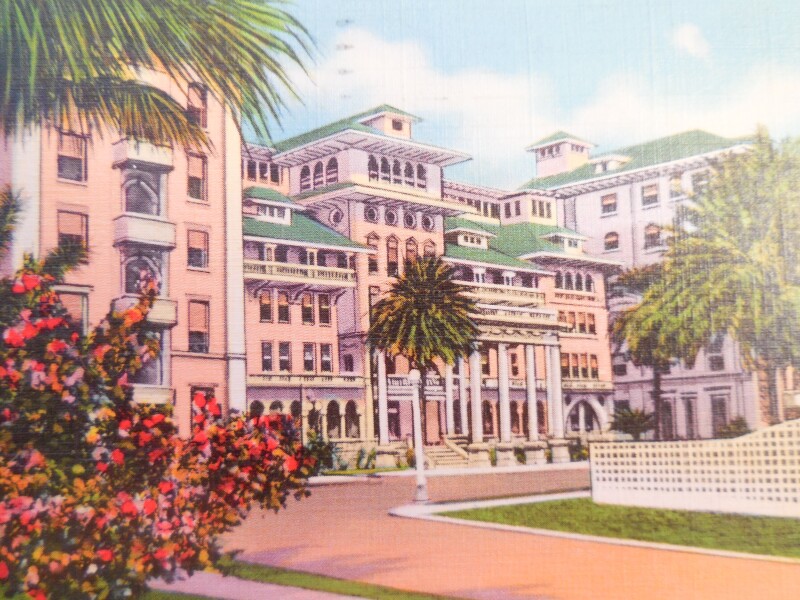

A serene view of Honolulu, sent soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor

Photo courtesy of Pat Tompkins

Colorful artifacts with history lessons

Postcards are synonymous with good times, yet they can hold a lot of history. A case in point: My mother saved every postcard she ever received; those from the 1940s alone made a sizable stack. Among them one caught my eye: It depicts the Moana Hotel in Honolulu in pastels, with a green roof and surrounding palm trees. A remote paradise, with not a person or car in sight. On the reverse, the sender’s address takes up half the message space; he’s a soldier stationed at Pearl Harbor. The date is December 29, 1941. The message: Jim hadn’t been able to locate her brother, a Marine who served in the Pacific. He signs off, “All is fine here.”

Her address in New Orleans, the house she was born in, has an extra line: “U.S.A.”; at the time, Hawai‘i was not yet a U.S. state. (After the December 7 attack on Pearl Harbor, the territory would be under martial law for several years.) There’s also a stamped notice in bold black: “Released by I.C.B.” That’s the Information Control Branch. The country had been at war only a few weeks, but already an organization was censoring mail.

Another snippet of wartime history re cards: Many sent to my future mom have no stamp, with FREE written in the upper right corner. (Starting in 1942, mail was postage free for those in the military.) And mail was important. U.S. households got delivery twice a day until 1950. Long-distance phone calls were expensive, saved for only very special occasions.

When it comes to postcards, the picture is often worth more than the 50 or so words that senders could squeeze into the message section. “Having a wonderful time. Wish you were here” was the standard text. Perhaps a comment on the weather, as one sender noted on a July 1943 card from Arkansas: “It’s hotter than you know what!” Yet those postcards were special, mementos worth saving from family and friends lucky enough to be traveling.

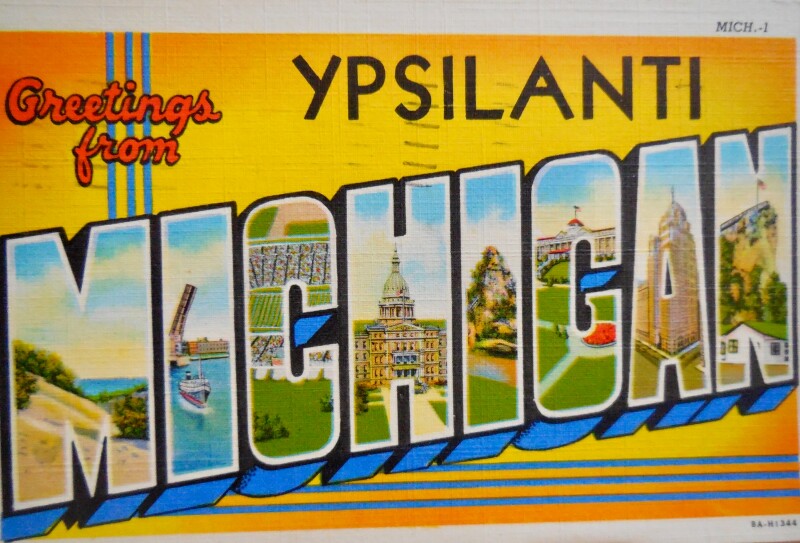

U.S. cities large and small used postcards to promote their attractions.

Photo courtesy of Pat Tompkins

Before World War II, postcards were generally colored illustrations (their heyday 1910–1940s) not photographs. They had a white border (like photos) that often named what was pictured. Today’s generic glossy color photo cards became popular around 1950. Besides being a fast way to send a message, postcards were often marketing tools, promoting travel to various places. Every city worth its salt sold a local “Greetings From” card depicting its wonders. For example, a Cedar Rapids (Iowa) card featured the Hotel Roosevelt and a Quaker Oats factory in the two Rs of its name. Atlantic City declared itself “The premier World’s Health and Pleasure Resort.” New Orleans? “America’s Most Interesting City.”

I continue to mail postcards to friends from my trips. And I continue to be surprised that something so small and flimsy can travel so far and generally reach its destination. During my first international trip in many years, I mailed a postcard from Stockholm to myself simply to see if it would arrive. (It did, and I still have it.) I also sent a card to myself some 30 years ago from Havasupai reservation in the Grand Canyon. I wanted a memento from the last place in the USA where mail was delivered by mules.