For a moment, the riotous swirl around me ceased. The whine of the snake charmer’s horn, the undulating hips of the transvestite dancers, the wafts of grilled lamb, the cries of the healer just in from the Sahara as he spread out ostrich eggs and gazelle antlers before him—it all stopped. Coco gave me an inscrutable look, rested her tiny hand on my shoulder, and then pressed her lips to mine. I was so stunned, I didn’t even notice as she slipped the water bottle from my hand.

There are not many places in the world where you can be kissed by a thieving monkey, but the Djemaa el Fna is one of them. A sprawling square at the thrumming heart of the Moroccan city of Marrakech, it has long seemed to me the most exotic place in the world—a fantastical spectacle where acrobats in satin pantaloons turn flips and dentists pull teeth, where drumming musicians spin their heads in trance, and multilingual touts no older than 12 try insistently to persuade unsuspecting tourists that they are licensed guides, where men in lab coats cook up heaps of wriggling snails, and storytellers regale listeners with the most marvelous tales.

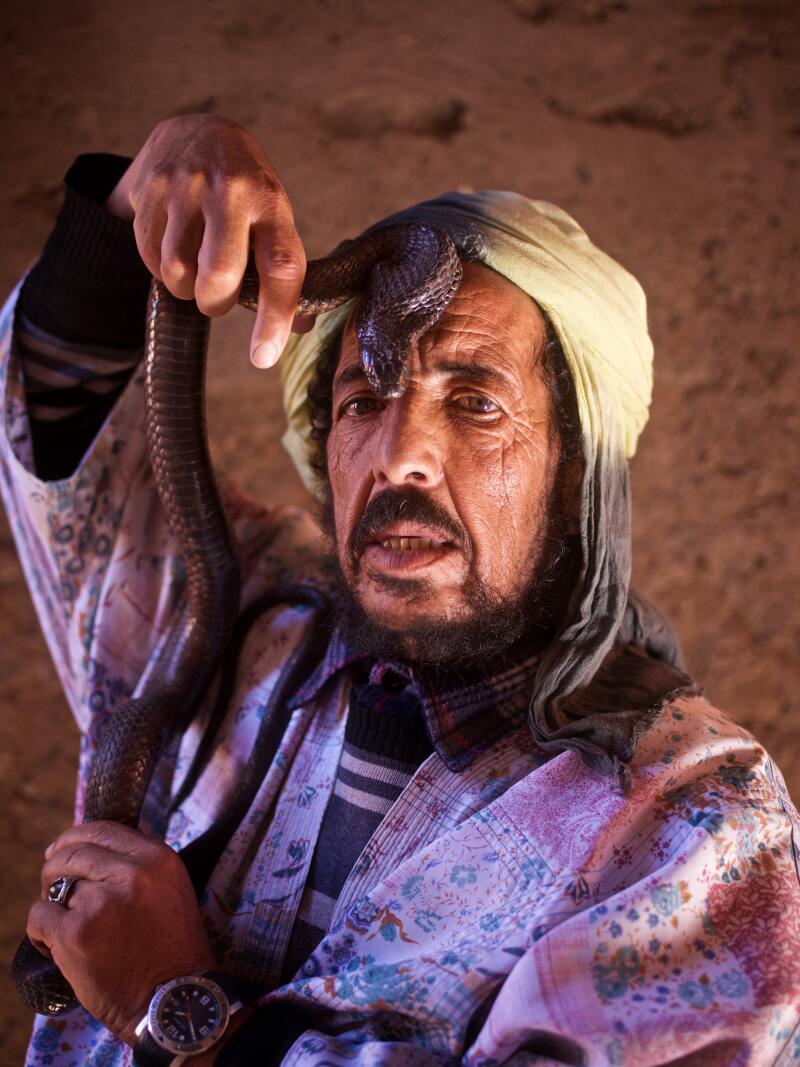

Farous Belaid, Snake Charmer

Photo by Robin Hammond

It is that exotic essence that has kept me returning regularly to Marrakech ever since my first visit 25 years ago. A dreary winter, or too many months stuck in a rut of work, would get me craving the kaleidoscope of sights and sounds and smells the city offers, and before I knew it, I’d be sitting at an outdoor café, sipping mint tea so sweet I could feel it carving cavities into my teeth, watching the scene unfold before me.

But “exotic” carries distance within its definition—it depends on finding someone or something different, or “other,” as the postmodernists like to say. And somehow over time, the idea of distance had lost its allure for me. I found myself wanting less spectacle and more connection. Would it be possible, I wondered, to go beneath the surface of the exotic? Could I get to know the people for whom the Djemaa el Fna was not a site of fantasy, but a part of their routine? Instead of strangeness and distance, could I find something familiar, even relatable?

My plan was simple: to hang out, and with the help of a translator, talk to people for whom the Djemaa el Fna was ordinary life. In other words, I would chat up those who worked there. The square, after all, has been a cosmopolitan marketplace since the Middle Ages, which means that there have been people making their living from it for just as long as there have been people coming to gawk at it. I hoped that by sticking around and asking questions—Is there a hierarchy among orange juice sellers? Do you get dizzy spinning your Gnaoua hat like that? How does one become a snake charmer anyway?—I might learn something meaningful about Morocco’s most iconic place.

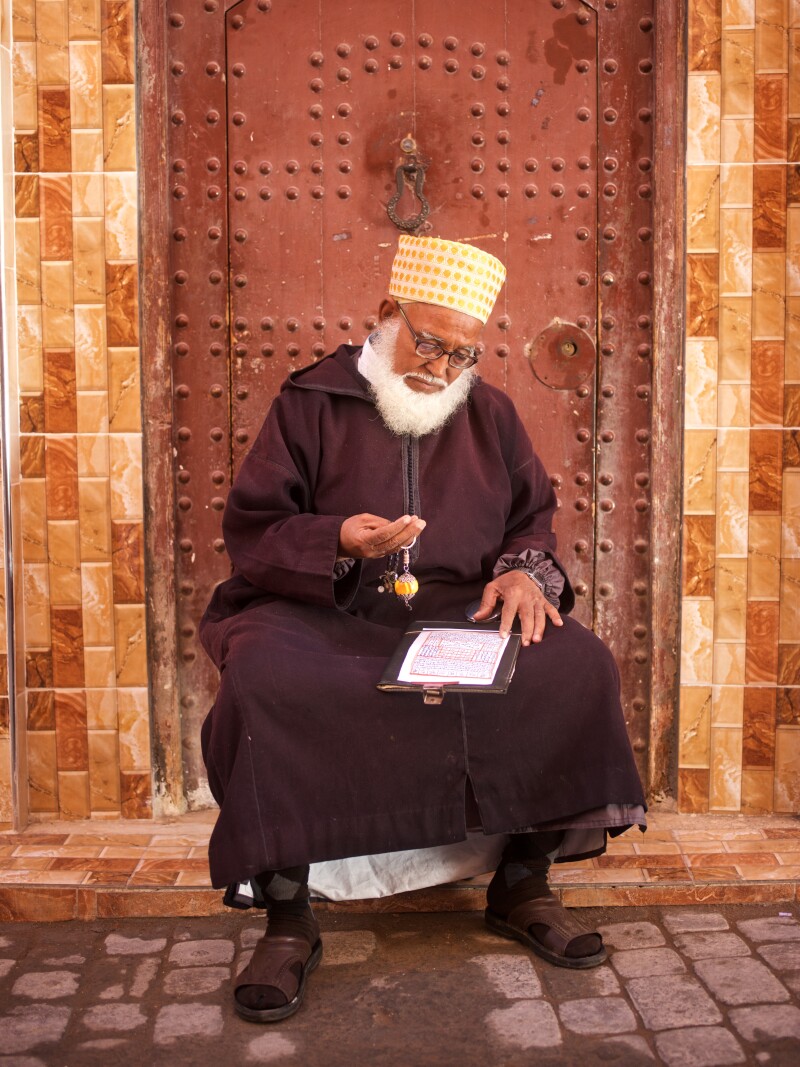

Abdelkabir Almou, Monkey Trainer

Photo by Robin Hammond

Instead of being content with the spectacle of Coco’s kiss, in other words, this time I set out to learn the story of the man who taught that monkey to pucker up.

Abdul el BarakaJuice Vendor

To the casual visitor, the Djemaa el Fna can appear timeless, but Abdul el Baraka knows that’s not true. He’s only 26, but has been working at juice stand #63 since he was 14. His father wanted him to stay in school, but he wasn’t doing very well there, and besides his family needed the money, even the little he earned back then. “When I started, I was only allowed to cut fruit, and made 20 dirhams (about $2) a day. I did that for two years before I was allowed to squeeze a single orange.”

That’s not the only change he’s experienced in the last dozen years. For one, the stand itself is different: When el Baraka started it was a pushcart, but now it’s more like a full-fledged food truck, with billboard menus and long stretches of fruit stacked alluringly. The offerings are much more diverse now, fruits and blends—kiwi strawberry, pineapple coconut—that go far beyond the basic orange and grapefruit el Baraka knew in the early years. And for reasons that no one remembers now, most of the vendors wear lab coats. “Probably one person started wearing it, and then everyone else followed,” Baraka says of his colleagues in the other juice stands. “That’s what happened with the pomegranates.” Pomegranates? “Yeah, one stall introduced a new flavor, and everyone else copied, “ he says, flashing the broad, gap-toothed smile that draws clients with magnetic force. “Even here, we have trends.”

Hajiba SwergyHenna Painter

She may spend her days tracing impossibly intricate designs with her narrow brush, but make no mistake: Hajiba is in it for the money, not the art. “It’s a job,” she says of the lacy vines and swirls she paints on the hands and feet of female travelers eager for a touch of Moroccan beauty. (Local women have their henna painted at home or in a salon.) “Anyone can learn it. I started when I was seven.” On a good day, she’ll paint three or four designs over the course of her 10-hour day, and earn about 400 dirhams ($40).

Abdelaati Alia, Talisman Seller

Photo by Robin Hammond

The biggest challenge of her job is attracting clients. Perched on a tiny stool, her feet clad in pink polka-dot socks and plastic sandals, she reaches out, unsolicited, to grasp the hand of a passing tourist, then, attention captured, quickly tries to engage her in conversation. “You have to be a psychologist,” she says. “You need to know how to talk to people so they trust you.” Her trick? “I ask about their kids.”

For her own children—she has four—Hajiba hopes for better things. “I wouldn’t want my girls to do this. It’s too hard. You’re outdoors all day, in the heat and in the cold. It’d be better if they become teachers.” As for her own aspirations, they tend toward the monetary. “I’d like to become rich. Inshallah.”

Jamal TaikaSnake Charmer

Of all the serpents in God’s kingdom, cobras are the smartest. Jamal learned that from his father and grandfather, who were also snake charmers. But it was proven to him 20 years ago, when it came time for him to catch his own. He went into the desert in March—“that’s when the snakes marry and have babies,” he says—and, per custom, fasted while he hunted. It took weeks, but eventually he caught one. “You have to think like a cobra,” he says of his method. “They like to follow movement, but they have a sixth sense. They’re sneaky. And they’re not loyal to anyone.”

There are five snake-charming families who work in the Djemaa el Fna, and together they make up what they say is the square’s No. 1 tourist attraction. They all get exercised when asked if they remove their snakes’ poison. Jamal’s own father died years ago, he says, of snakebite, and his colleagues echo his disgruntlement when he brings up another charmer who died recently because the hospital where he was taken after being bitten allegedly had no antivenom on hand. Even so, he’s not afraid of the animals. “The snake is the enemy to everybody else. But to us, he’s a friend.”

Brahim el Chaouef, Water Vendor

Photo by Robin Hammond

Abdel Fattah SiddikMint Vendor

Unlike most of the square’s workers, Abdel devotes himself entirely to locals, not tourists. His stall—one of five selling herbs—is piled high with bunches of the fragrant mint that Moroccans use to make tea. The omnipresence of that drink—which finishes every meal and is a necessary social lubricant for everything from business transactions to outings with girlfriends—helps explain why Abdel sells so much of it. That and his good nature, explains one client: “I’ve been coming since it was his father’s. They’re a nice family.”

But things are getting harder for him. He wasn’t on the square the day that terrorists set off a bomb at the Argana Café a few feet away, killing seventeen people, but his dad was, and he’s been concerned about security ever since. “There are more cameras, and more police, but the worry never really goes away.” An even greater worry is changes in consumer habits. “It used to be that everyone came here to do their shopping,” he says. “But now people go to the supermarket. Everybody still needs mint, they just don’t need it from here.”

MahjoubShoe Shiner

There are 15 shoe shiners licensed to work in the square, and Mahjoub (who would give only the one name) is #5. Shoeshines used to be one among many services locals could get the square. At 72, Mahjoub remembers when there were barbers there cutting hair and dentists pulling teeth, but these days he and his coworkers are all that is left. His experience—all 61 years of it—shows in the way he coolly sizes up a customer, caressing a shoe’s leather like a lover, and quickly pulling the proper brush and polish from the collection he keeps in a scuffed wooden box. He works silently, a slap to the side of the box the only indication that it’s time for the client to change feet.

Mahjoub is not one for small talk. But when asked about the faded Arabic tattoo on his arm, he explains, “It says THE INJUSTICE THAT MADE ME CRY.” He got it after he was jailed—unfairly, he says—for getting into a fight over a woman. He spent three months in prison, “but it seemed like forever, because I was in love,” he says. Asked whether the woman waited for him, he chuckles. “She’s waiting still.”

Touria Moutalib, Balloon Seller

Photo by Robin Hammond

Jawad AbdelghafourGnaoua Musician

Although only a teenager, Jawad Abdelghafour knows he has power. In fact, he’s seen it: A Gnaoua musician, he and his colleagues have freed victims before his eyes from the bad spirits that plague them. The music itself “is more African than Arab,” Jawad explains. “That sound?”—he clacks the castanets known as krakeb—“It’s the sound their chains made when the slaves danced.”

But Gnaoua isn’t just music; it’s also a spiritual practice. The musicians are hired by an individual or family suffering from illness or another misfortune. The ritual begins at sunset with an animal sacrifice. Throughout the night, the musicians play through seven “colors” until the spirit associated with the affliction reveals itself, and frees the victim. “It doesn’t scare me,” says Jawad. “The spirits have to listen to Gnaoua.”

When they are not conducting the rituals or performing at festivals or in hotels—Gnaoua music is very popular in Morocco these days—Jawad and his colleagues don their tasseled hats embroidered with cowrie shells and play in the square. “Whoever likes it,” he says of the music’s fans, “lives it.”

Hassan KharmouchGame Organizer

He is a man who dreams of the sea. In the Djemaa el Fna, the only water Hassan Kharmouch sees comes in the goatskin sacks of sellers with fringed hats, and these days⎯when they can make more money by posing for tourist pictures than by quenching anyone’s thirst⎯he may not even see that. But once, Kharmouch spent his days on the ocean: He was a fisherman who spent his days hauling up octopus off the coast of Dakhla. He had his own boat, but the low prices paid by distributors drove him out. “It was too hard to make a living,” says the 29-year-old.

Jawad Abdelghafour, Gnaoua Musician

Photo by Robin Hammond

Instead, he now makes his living by running a game of skill in the Djemaa el Fna. He sets up a circle of bottles of soda. In exchange for 10 dirhams (one U.S. dollar), his customers get 10 minutes to attempt to hook the bottle via a ring that, if angled properly, slips over the bottle’s neck; if they succeed, they get to keep the soda. The ring, it should be said, dangles from a long, makeshift fishing pole. “What can I say?” Kharmouch explains with a shrug. “I miss it. The sea is a different world. It’s a beautiful world.”

Aziz RamzeyAnimateur

By late afternoon, the eastern edge of the Djemaa el Fna is a hot, smoky, noisy hive of activity as dozens of makeshift restaurants set up tables and chairs, build kitchens, and lay out displays of kebabs, salads, tagines, fried vegetables, and fresh fish in preparation for the dinner rush. It also becomes something of a gauntlet for any passerby hungry or curious enough to get within a few meters. Thanks to dozens of persuasive talkers known as animateurs—each one hired to lure potential customers to a particular stall—walking through the vicinity can feel like a siege. But that, says Aziz Ramzey, is because most of the other animateurs don’t know what they’re doing.“I’m the best,” he says with the assurance of someone who has spent the last 20 years honing his skills. “Maybe there’s one guy who’s better than me, but otherwise, I’m the best.”

The full tables at Restaurant #15 seem to bear him out. By common understanding, each animateur is only allowed to work within a fixed perimeter of the stall that employees him, so most congregate at the outer edges of their territory, in order to get maximum exposure to potential clients. But Aziz hangs back, confident in his technique. I see it in action when he learns I live in Denmark. “Eat here,” he says with a smile. “It’s better than Noma.” Later he confesses to having an arsenal of such remarks. “If you were from France, I would have said Paul Bocuse.”

Abdelkabir AlmouMonkey Trainer

The family of Abdelkabir Almou has been in the monkey business for 40 years. Like his parents before him, Abdelkabir keeps his monkeys at home, in cages hung in the trees of the garden patio of his house. He’s got 23 or 24 total—he can’t remember which. They all come from the Atlas Mountains.

Khadija Hedidi, Fortune Teller

Photo by Robin Hammond

Coco, he says, is his favorite, because she was born on the same day as his son, seven years ago. She can do a dozen tricks, including kissing, smiling, flipping, and her signature pose, At The Beach, in which she stretches out coquettishly, as if sunbathing. “They’re not that hard to train, because they’re good imitators,” he says of the monkeys. “You just use food as a reward.” Coco likes cheese especially.

He hopes his sons choose a different profession when they grow up. “It can be hard,” he says of his job. “I get a lot of criticism from tourists who think we mistreat the animals. They can be very aggressive.” Pulling Coco onto his shoulder for a kiss, he shrugs. “They just don’t understand.”

Neither, he would later tell me, does his wife. Early on the morning before I was to leave Marrakech, I ran into Abdelkabir in the medina. Coco must have been at home, because he was alone. In broken English and French, he told me that he had had a huge fight with his wife, and that she had thrown him out. He had been sitting in the café all night with no place to go, worrying about when he would see his family again. I told him how sorry I was to hear about his troubles, but inside, I was skeptical: I had been in Morocco enough to know that tourists are often scammed. My doubts faded, however, when he began to sob. I opened my arms and for a few moments, there on a silent street off the Djemaa el Fna, the monkey trainer and I embraced.