This story is part of Travel Tales, a series of life-changing adventures on afar.com. Read more stories of transformative trips on the Travel Tales home page—and be sure to subscribe to the podcast!

“OK, Eleanor,” I say, fighting back a sneeze from the spice stalls and the other smells of Istanbul’s Grand Bazaar, surrounded by men smoking, arranging themselves like birds on a wire while their wives gawk at wedding dresses that seem to have been made of marshmallows.

“OK, Eleanor. This is for you. For you, I’m going to bargain. I’m going to haggle. I’m going to buy. I owe you this one.”

I’m on a mission.

When I was a kid, my mom’s sister, Eleanor, would appear on our doorstep as unexpectedly as a lawn flamingo coming out of a magician’s hat. She’d confetti the air with coins from extinct countries, arm us with Gurkha knives and lion spears. She’d tell us about riding elephants in India, about watching women in bowler hats chase wild llamas in the Bolivian mountains. From the 1960s into the 1980s, Eleanor traveled the world alone, armed only with a courage that took me years to truly appreciate and a bra stuffed full of local currency, leaving in her wake stall dealers and vendors laughing about the stuff the short fat American bought.

By the time her final days rolled around, she shared her apartment with every incredibly tacky thing offered in every market across five continents: bowls that leaked, candlesticks that fell over, ponchos full of moth holes that actually improved the fabric pattern, salad tongs that should have stayed trees, and pipes and hookahs and all the equipment necessary for a dozen vices she didn’t have.

The family fights began before the funeral was even over. “You take it.” “I’m not gonna take it, you take it.”

I took nothing. In our last conversation, she asked what I wanted. “You gave me the idea that the world is a playground,” I said. “I don’t need things.”

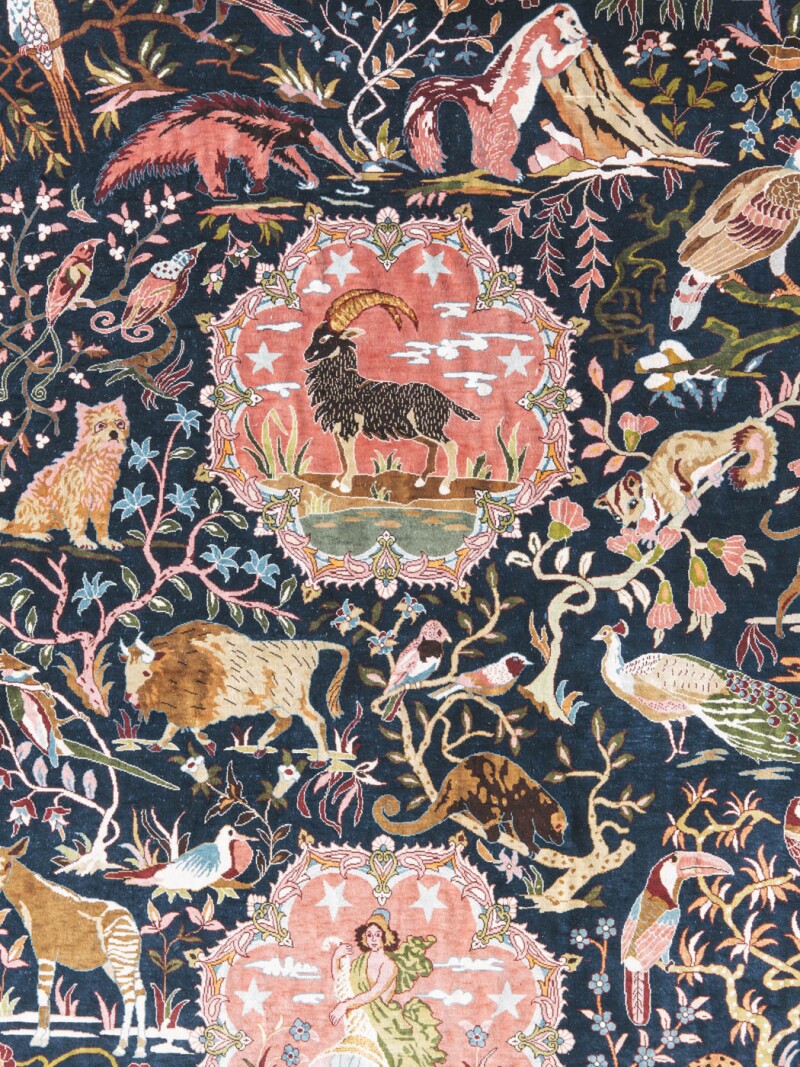

But lately, I’ve been wondering. Did I underestimate her taste the same way I did her courage? Was the Turkish carpet—made, as best I could tell, of wool dyed in Pepto-Bismol—that she’d unroll to bring us the world perhaps not really just a place to sit? Maybe it was a door I didn’t look at long enough. Because after 25 years of serious travel, after I’ve seen maybe double the number of countries Eleanor went to, pretty much all the souvenirs I’ve ever bought would fit in a shoebox.

Yet, even if I don’t have anything I chose myself, I do still have those little memory bombs of Eleanor—long-ago days, sprawled on the Magic Pepto Carpet while she’d show me a postage stamp of exotic animals, a coin with the image of a king who had already been erased from the books. Eleanor’s rule number one: There’s always time to sit and tell stories.

Now, for my own memory of Eleanor, I’m going to buy a carpet of my own—to prove that souvenirs don’t have to be tacky. To leave behind something that the family will fight over with avarice. And maybe I’ll find that one thing that will frame my memories of my travel, the still spot in the world where it all began with my favorite aunt.

I wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for her. So let this story start.

Photo by Dustin Aksland

“We were born with the carpet, we grow with the carpet,” says Hakan Hoser at the gallery Hereke Hali, just outside the Grand Bazaar. On my first try in the shopping maze, I lasted less than 15 minutes before fleeing like I had the last scoop of brains in a zombie movie, chased by salesmen yelling, “Carpet, you need carpet, we have best quality!” But here, the gallery is hushed; carpets come and go as if piloted in when I wasn’t looking.

In the glory years of the Ottoman Empire, home began with the carpet. They were beds, pillows, and vital parts of every dowry. Some were woven in designs so sacred only the royal family could possess them. Others, slung as cradles, rocked babies, and one’s first exploration of the world was crawling across the geometry of fine weaving, a way of learning early that the world is mostly soft, with exquisite detail.

What sets the Turkish carpet apart from, say, its Moroccan or Nepali cousins, is not just the patterns, the intricacy and language of thread, but the technique. For every other weaver in the world, it was good enough to weave the woof (horizontal) thread once around the warp (vertical) thread. But, in a tremendous fit of 6th-century masochism, Turkish weavers decided one knot simply wasn’t enough, and they went back around for a second time. It left generations of women with hands like lobster claws. But it also left an end result of almost indestructible rugs, ones that shine like a prism catching passing light. Related How to Buy a Turkish Carpet in Istanbul

“One hundred sixty-four tribes were subjected to the Ottomans,” Hakan says, “and each area had its own designs.” He spins out silk-on-silk carpets—“up to 4,000 knots per square inch.” Then wool on cotton—“perhaps 500 knots per inch.” Each knot slowly builds toward meaning. An oil lamp in the design rep- resents celestial light; woven pomegranates signify abundance in their scatter of seeds; a careful arabesque of knots bounces the evil eye back to the sender. Colors were made from the landscape of home itself: blue from cobalt, tan from crushed walnut shells, golden yellow from saffron, a single gram of it enough to tint 100 kilograms of wool. “Move to the east,” Hakan says, “the colors get darker. Move to the coast, you can see lighter colors.”

Could my shopping trip be this easy? We spend a happy hour sipping tea, and after looking at perhaps a hundred carpets or more, I have the choice down to two. One has a bright red center panel; inside are geometric designs like diamonds at play inside a field of flowers. The other one is even more abstract, a tree of life or a game of Hangman that went bad.

Yeah, these could be my magic carpets, like Eleanor’s Pepto number.

Years ago, I worked for an art dealer. I also spent decades selling rare books, books as art. Maybe that’s why I don’t buy, because I learned to sell, to let things pass through my life. But I have also taught customers that the way to shop for art comes down to just one simple rule: If you fall in love, you buy, and you never regret it. But if you hesitate, it probably wasn’t love at all.

Photo by Dustin Aksland

And I am in love with these rugs. I respect this dealer and his shop. I know I would never get tired of looking at these rugs. I close my eyes, and it’s the trees that linger, so I’ll buy the stick-figure design and spend the rest of my trip looking at Byzantine mosaics. Mosaics make a good story of the place, each tile adding to the design like the knots on a thread.

Which is when the dealer makes a fatal mistake. “Let me show you one more, just because it is beautiful.” And oh, oh it is. It is. The pattern is like the architecture of a cathedral done in reds and blues. It makes the other two carpets look like 1970s shag.

“The carpets are a dying art,” Hakan says. “The number of looms is getting less and less every year. The ladies would rather do something more profitable.”

And then he names his price. It equals two months of my rent back home. Is that what tying a couple million knots is worth?

In the glory years of the Ottoman Empire, home began with the carpet.

It is definitely more than my credit cards allow. But wait, that’s why I came here: to haggle. I take a deep breath, and make a counteroffer. He just shakes his head. “We could talk five more minutes or another hour, the price won’t change,” he says. But he lets me take a picture of the rug, and clearly he’s happy that he showed me something I like so much. Forget the sale. Share the beauty and give thanks for this chance to share in an art that’s fading away even as we speak.

The question becomes, if you’ve seen the absolute best, why bother with something less? That’s why I walked out of Hakan’s shop. That one’s my dad’s rule—buy well, buy once.

My dad would not last five minutes here. Buying a Turkish carpet requires the stamina of a marathon runner. A single city block can sport a dozen shops, and there’s no escape until you’ve looked at dozens of rugs, drinking at least two cups of tea while the rugs lay their beauty out like a tray of Turkish delight.

Each shop is also an exercise in keeping silent—never start bargaining until you genuinely mean it—and training the eye while narrowing the wants. After three or four shops, you can tell at a glance the quality of the carpet by how crisp the design is; after a few more shops, you know the feel of 500 knots per square inch versus 200. Most of the rugs I’m looking at are maybe 50 years old, relics of the time before everyone worried about time.

By noon, I’m comfortable with the fact that for the size rug I want—about four feet by seven—opening price will be between $1,500 and $3,000, depending on the shopkeeper’s hope of how full my wallet is. A Turkish law dictates how high an opening price is allowed compared with reality, but who knows what it is. As for me, I’ve set a limit: I can buy a rug equal to about one month’s rent. Which would make it the most expensive thing I’ve ever bought that doesn’t have an on/off switch.

Photo by Dustin Aksland

Each time I linger at a rug in Istanbul, the dealer will tell me it’s from Konya, in the center of the country. More rugs appear quickly, icky floral motifs, the smell of mothballs. If I pause, it’s Konya, always Konya.

And then I find out Konya is where the whirling dervishes are. And where the Sufi poet Rumi is buried. And I can fly there for less than 50 bucks. And I do fly there, on 50 bucks of hope that despite what everyone said back in Istanbul—that there simply are no weavers doing fine work anymore—some kind of traveler’s luck would hold and I’d magically end up surrounded by weavers.

You don’t hear “Rumi” in Konya. In his adopted home, he’s Mevlana—saint, mystic, and, 700 years past his death, still probably the best-selling poet in the world. “My soul is from elsewhere, I’m sure of that, and I intend to end up there,” Mevlana wrote.

Born in Afghanistan during the world’s war with the Mongols, Mevlana inherited his father’s post as a professor of religious sciences in 1231, but wandering feet brought him to Konya, where he met Shams of Tabriz. Shams introduced him to Sufism, an Islamic creed based on mystical, ecstatic expressions of devotion: music, poetry, and the whirl. Related On the Water in Istanbul, Where Two Continents Meet

“There,” says Cengiz Kellekci, pointing to a street corner. “That’s where Shams and Mevlana met.” I’d met Cengiz, a travel agent, through one of the rug sellers in Istanbul, a Konya man who’d called ahead on my behalf. But when I ask Cengiz about carpets in Konya, he looks at me like I’m joking. “No, all gone.” From what I gather, I could have landed anywhere in the country and gotten the same answer. Why doom your grandmother to carpal tunnel syndrome when you can buy a factory-made kilim, a single-knot rug, at the department store?

A younger version of me would be disappointed, or at least make a note for my future self: Do more research. But Cengiz is proof that sometimes you really do get what you need. With no grandmothers and their looms to track down, he shows me the rest of his world: museums of carpets and musical instruments, facades carved in script carrying secrets down the centuries.

And the tombs. So many tombs of so many Sufi saints.

Photo by Dustin Aksland

Near the town’s foothills, an entire neighborhood has turned out at Atesbazi Veli Turbesi, the local saint’s tomb, for the last day of Muharram—which is Ashura, the day of remembrance. A couple hundred people stand around a pickup truck, springs sagging under the weight of huge barrels of what is apparently every nut, every bit of sugar for miles around, all cooked down into a porridge.

I’m quickly spotted, bowed to—right hand over the heart—and taken to the front of the line for a bowl. A couple of men gesture to space on their patch of curb. To share in the nazri is to commune with God, and I hope among her rugs and salad sporks and emu-egg Christmas ornaments, Eleanor also had this souvenir: a moment of sharing in a life you hadn’t known before to even imagine.

By the time I get to Mevlana’s tomb, the sun is starting to soften. The poet’s sarcophagus lies covered by a huge, heavy blanket in a thousand shades of gray, as if the afterworld were cold. The walls behind are decorated with calligraphy, the perfect genre for a man of words. But I’m more interested in his actions, such as the time Mevlana whirled at a funeral, motion celebrating the meeting of soul and heavens. And the whirl goes on.

In a specially built theater in the round, maybe a mile from Mevlana’s tomb, the dervishes walk slowly into the room’s heart while a man sings in one of the most haunting voices I’ve ever heard; if wolves understood canto form, they’d sound like this.

Then the dervishes begin to turn. One moment they’re still, the next they’re a blur, a dozen men, arms upraised, whirling smoothly as ballerinas. They cock their heads to the right, their white robes billowing to make a sail to catch the music. The twirling seems mostly a matter of flexible ankles on a three-step—but how on earth do they keep their arms over their heads like that for so long?

Mevlana’s poem explains: “Your legs will get heavy and tired. Then comes a moment of feeling the wings you’ve grown, lifting.”

Almost anywhere you go in the world, ritual movement runs clockwise. The dervishes, though, spin counterclockwise, as if coming around to meet the world face to face, to greet its arrival. As Mevlana says, “We have gone to heaven, we have been the friends of the angels, and now we will go back there.” All of which seems like what I want from the carpet. A place to meet the world face to face, like I did when I was a little kid, and Eleanor’s stories sang off the Magic Pepto rug.

Photo by Dustin Aksland

Back in Istanbul, I do the small-shop shuffle for another day, but my eyes are starting to hurt from looking at so many bad rugs. Finally, I walk into the biggest carpet store I can find, figuring that to finance that much urban real estate, the merchant is either a highly skilled thief or has good carpets.

It turns out the shop, Sedir Art Gallery, has really good carpets. I’m quickly settled in with the inevitable apple tea—I’ll actually miss this stuff when I go home—and the show begins, three assistants twirling carpets like pizza dough, unrolling fields of color, flowers, trees, minarets. They bring more.

“If you don’t see the fish below the water,” the shop owner, Bayram Karaselek, says, “there is no reason to start negotiating.”

We quickly narrow down my taste: Konya, dark colors, architectural. “Not a prayer rug but prayer design,” Bayram says. His assistants go to the corners of the room, grab a half dozen rolled carpets. Out comes one with a central lozenge shaped like the heart of the last star I remembered to wish upon, a blank spot surrounded by a riot of design.

My rug. I can hear it breathing.

But not wanting to tip my hand so soon, I wave away some—but not all—of the other rugs, saying, “How about that one? And that one?” At last I point to this four-foot-by-seven-foot chunk of paradise.

Maybe I’ll find that one thing that will frame my memories of my travel, where it all began with my favorite aunt.

He quotes a price that is equal to six months of my rent. I’m very proud of myself for keeping a straight face. “I can only offer a price that would be an insult to you,” I say.

One month’s rent.

Bayram does not keep a straight face, but he doesn’t really have anywhere else to go, either. Assistants toss more rugs out as bait. Cast and reel, cast and reel. Bayram offers other prices. I stick to mine as we look at these products of the fine generosity of sheep and the artisan hands of ladies.

“When you walk on something beautiful, you want to feel it,” he says. “Take your shoes off.” Even that’s not enough; we end up lying down on the rug to truly experience how soft the thing is. A low-quality rug, he tells me, takes about four months to make. One of this quality takes eight.

At last, after two hours of me saying “That’s all the money I have,” Bayram laughs. “And what if I offered to sell it to you for one dollar more?”

Photo by Dustin Aksland

“Then I’d say thank you, but I can’t buy your rug.”

And he laughs again, gestures to his assistant, who starts folding it in a particular origami that means SOLD.

I’ll take it home. I’ll stake it out as the center of my universe. Eventually, my nieces and nephews will have children who will puke on the rug, puppies that will chew the corners. Because you live with the rugs.

As for me, until that happens, I’ll remember Eleanor’s love of all the pieces of the world she carried home, including her own Pepto-pink rug. I’ll spin on the carpet with the angels, catch the world coming around the other way, and smile, joyful at the meeting.