We’d been following the Muhoza family of 18 mountain gorillas for about a half hour in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park, observing younger apes practice climbing trees, adults munching on bamboo shoots, and the broad-shouldered, 400-pound dominant silverback keeping a watchful eye on the scene. A few members of my small hiking group took notice of a new mom, who seemed content to cradle her newborn in our midst.

“It’s like she wants to show him to us,” one of my companions whispered as we crouched behind some ferns, mere feet from where the mother was cuddling with her month-old baby.

She rolled onto her back and placed the babe on her chest as if to offer us a better look. While we took photos, she gently rubbed its back and kissed its fuzzy crown, and the infant blinked its soft brown eyes curiously at our lenses peeking through the leaves. We found it hard not to anthropomorphize them—after all, they’re our closest neighbor in the evolutionary lineup. To me, the movements, social interactions, and the gaze of the gorillas seemed surprisingly humanlike.

I had traveled halfway across the world for this very moment. A longtime enthusiast of wildlife conservation, I had always dreamed of visiting the remaining habitats of the roughly 1,000 mountain gorillas left in the wilds of Rwanda, Uganda, and the Republic of the Congo. As I stood near the Muhoza family, hearing their playful hoots and watching juveniles wrestle while the elders tried to groom them, I oscillated between the urge to capture every moment on film and the desire to simply be present. I had just started a five-day trip with Volcanoes Safaris, an ecotourism company that operates four (soon to be five) lodges, one in Rwanda and three in Uganda, to learn about gorilla conservation. What I didn’t realize during that epic wildlife encounter was that my trip, which would also take me across the border to Uganda, would reveal the extent to which the future of gorillas is connected to the fate of the communities that coexist with them.

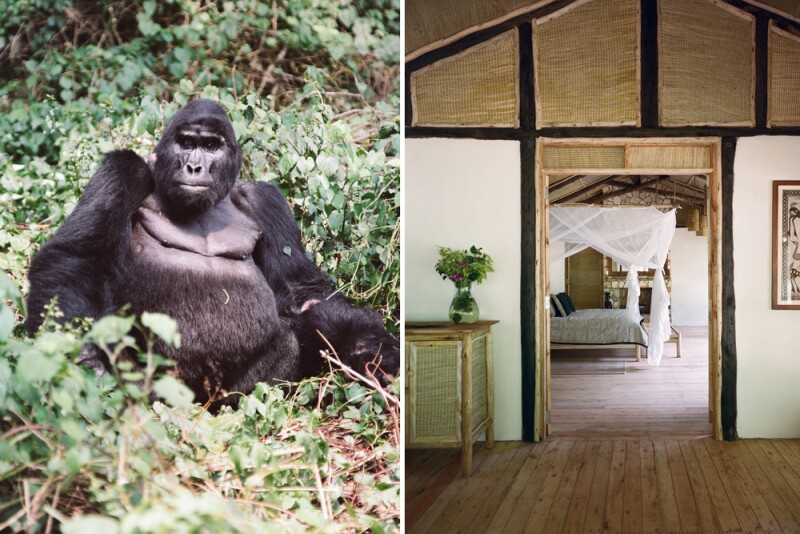

Three of Volcanoes Safaris lodges are near gorilla habitats, the other is near chimpanzees.

Courtesy of Volcanoes Safaris

Back at Volcanoes’ Virunga Lodge in Rwanda, I learned about the region’s early conservation efforts in the Dian Fossey Map Room, a permanent exhibition area that charts the work of explorers and scientists who have lived and worked in what is now Volcanoes National Park. The space, which doubles as a dining room, was named after a conservationist who spent 18 years in the Virunga Mountains studying and protecting the great apes. It sits on a more than 7,000-foot-tall ridge facing the verdant Musanze valley, Bulera and Ruhondo lakes, and the neighboring park’s tree-covered volcanoes. Virunga Lodge was the first accommodation for international travelers to open in Rwanda following the 1994 genocide, a civil war between two ethnic groups that killed close to 1 million people. It’s hard to believe that today, almost 30 years later, the area is now home to some of the most well-known names in luxury safaris, including Singita Kwitonda Lodge, One&Only Gorilla’s Nest, and Wilderness Safaris Bisate Lodge. Founded 25 years ago by Uganda-born Praveen Moman, Volcanoes Safaris (a 2022 AFAR Travel Vanguard winner) is often credited for being one of the first companies to revive the region’s tourism industry.

The lodge is located 40 minutes from the entrance to the park and the adjacent Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund’s new center for conservation, science, and tourism. We were lucky enough to be there for the grand opening of the Ellen Degeneres campus on our first day. Dr. Tara Stoinski, president and CEO of the Fossey Fund, told us this campus couldn’t have come at a more critical time. “We’re in the midst of the sixth mass extinction of biodiversity on the planet, and all the data is telling us how important conservation activities are,” she said. “This campus serves as a training ground, not just for Rwanda, but internationally. A place where we can bring career scientists together to think about what are the solutions for conservation.”

For two decades, Volcanoes has worked with the Fossey Fund to connect travelers to the great apes and showcase how conservation and tourism go hand in hand. In the 1980s, mountain gorillas were on the precipice of extinction and would now be gone had it not been for Fossey’s work. Today gorilla conservation depends on critical tourism dollars for protection and research: To visit the gorillas in Rwanda, travelers must purchase a trekking permit, which costs $1,500 per person. Three-fourths of the fee goes toward gorilla conservation, 15 percent goes to the government, and another 10 percent goes to communities that live near the country’s four national parks.

Community benefit is the part of the conservation equation that Moman believes is crucial to the future protection of the region’s wildlife and landscapes. And it’s the connections I made with these very communities that made the trip so eye-opening for me. One night at Virunga Lodge, we gathered atop a grassy hill to watch the Intore Dance Troupe perform the traditional victory dance of Rwandan kings. Before the setting sun and to the steady beat of drums, men in long headdresses made of dried grass meant to mimic a lion’s mane danced, jumped, and spun across the summit with flat-tipped spears and small shields in hand. The group is compensated through the Volcanoes Safaris Partnership Trust, a program started in 2009 to create entrepreneurial initiatives geared toward conservation while providing income to nearby communities. The trust has supplied hundreds of clean water tanks, upgraded local schools, gifted nearly every family with a sheep (used for their natural crop fertilizer and milk), and offered vocational training for those who wouldn’t otherwise be able to access it.

From Mount Gahinga Lodge guests can trek to see gorillas and meet with the Batwa people.

Courtesy of Volcanoes Safaris

After a few days in Rwanda, we took our safari vehicle on a quick, albeit bumpy 20-mile journey across the border into Uganda to stay at Mount Gahinga Lodge. Nestled at the base of its eponymously named mountain, the lodge is composed of eight stand-alone suites, each adorned with thatched roofs and windows facing the peaks. It’s an easy jumping-off point for climbing a volcano, tracking golden monkeys, and trekking in Mgahinga National Park, where there is only one family of nine gorillas. (To my delight, we did another trek, spending three sweaty hours searching for the animals before we found them all napping in a grove with bellies distended from a fruit feast.) It’s also one of the few places where guests can interact with the Batwa people, the oldest inhabitants of the Central African rain forest.

The Batwa are an Indigenous community that lived for millennia in harmony with the gorillas, in the mountains that straddle the Rwanda and Uganda border. They were evicted in the ’90s when the national parks were created. They were unable to fit into modern Ugandan society, as they’d primarily been hunters and gatherers on land they could no longer access, and didn’t speak the local language. So they became conservation refugees living in makeshift shelters—a humanitarian crisis nearly 30 years in the making.

Moman eventually developed a relationship with one of the Batwa tribes and helped them resettle through the Partnership Trust. Although mountain gorilla tourism was the catalyst for the Batwa’s removal from their homeland, at least for this group of roughly 100 people, it’s become part of the solution. Moman purchased land near the Mount Gahinga Lodge, brought in an architect to build permanent housing, and gathered the necessary resources for them to farm.

One afternoon, we walked the serpentine trail behind the lodge to meet with the Batwa at their new village. As we walked, I told Ronald, one of the staffers who served as our guide, that I was nervous—I didn’t want the Batwa to feel exploited by my presence. He nodded and explained the experience intends to teach visitors about why it’s important to support those who have been marginalized as a result of conservation. Allowing the Batwa, and the other communities Volcanoes serves, to be part of the economic mainstream in turn helps the gorillas survive.

The Batwa became conservation refugees after the national parks were developed.

Courtesy of Volcanoes Safaris

As we approached the village, the Batwa greeted us with song, and Jane Nyirangano, their chief, beseeched us to ask any questions about their lives, past and present. They guided us through their open-air community center (which, judging by the blackboard, had recently been used for grammar lessons) and to a modest store where the women sold their woven baskets. We were also shown the Batwa Heritage Trail, which consists of an herbal garden, a clutch of traditional huts, and a path where the Batwa can demonstrate how they used to live in the forest, both to visitors and their own children. When it was time to go, they walked us back to the lodge. As we made our way along the trail, I realized my time with the Batwa would be one of the most vivid memories of my trip—and the reason I’d return home with an understanding of the human story behind wildlife conservation.