Each year, hundreds of thousands of books are published in the United States alone. Around the world? Millions. But there’s a voice missing, even among all those titles, says Mondiant Dogon: those of refugees.

Born in 1992 into a Congolese Tutsi family in the Bagogwe tribe, Dogon and his family were forced to leave their village when Dogon was three; by this time, the Rwandan genocide against Tutsis had spread into the Democratic Republic of Congo. (Tutsi are a minority ethnic group, and after a 1994 assassination attempt on Rwanda’s president, Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu, “Hutu extremists launched their plans to destroy the entire Tutsi civilian population,” per the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.) Then, Dogon and his family traveled to the Mudende refugee camp in western Rwanda, where they survived two massacres by armed groups from the DRC before being moved to a refugee camp in northern Rwanda called Gihembe. In time, Dogon would eventually flee back to Congo in search of his former life and become a child soldier before returning, once again, to Gihembe.

Back in Rwanda, Dogon attended a Rwandan high school and graduated at the top of his class, earning a degree in French and literature from the University of Rwanda. In 2016, he would meet an American businessman who changed the course of his life by helping him apply to New York University, which Dogon attended from 2017 to 2019, graduating with an MA degree in international education. Today, he works as a human rights activist and public relations specialist for a software company. He has been in the United States for four years, but the memories from his childhood are never far away.

Throughout it all, Dogon has been journaling; writing his story. The end result? A new-as-of-this-month title, Those We Throw Away Are Diamonds (Penguin Press), coauthored with reporter Jenna Krajeski. Writes Dogon: “I started writing my book because I wanted to reach other people—people who had no connection to us, who were not from Congo or Rwanda, not from Africa, who had never met a refugee or thought about what a refugee camp might be like. I wanted to reach them and let them know that we are still here. We have a lot to say about how the way the world works.”

With this in mind, we sat down with Dogon to discuss home, the U.S., and more.

You started writing this memoir in 2013, and the title is from a poem you had written. How important has writing been to you?

Prose and poetry have played big roles in my life. I started writing prose before poetry. But poetry for me was the main tool I used when I wanted to deliver a message with rhythm and rhyme. Because especially back home in Africa—where you may write something that puts you in conflict with government—I had to balance and think about the best way to write and convey the message I wanted to share with the world.

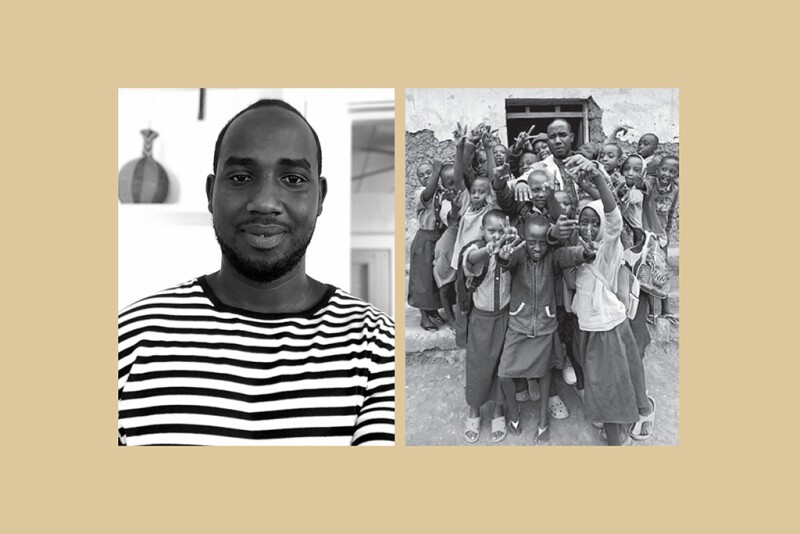

From left: The author at home; at a children’s school in Gihembe

Photos courtesy Mondiant Dogon

As travelers, one of the most common questions we get is, “Where are you from?” How do you answer that?

That is a very difficult question for me. I was born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, but spent my life in refugee camps—and my home country, Congo, doesn’t accept me as a Congolese: I went to the Congolese embassy at the United Nations in New York, and the embassy told me that I am not Congolese. But I say I am Congolese.

How has your perception of the United States changed since your arrival?

A lot has changed. Back in Gihembe, I faced so many limitations because of being a refugee. I didn’t want people to know who I was, especially my classmates or my fellow Rwandans. I knew the bad stereotype that many people have about refugees. But since I arrived in the States [in 2017], I saw that things are very different. I met people who understood me, supported me, and were eager to hear my story. That helped me to accept and embrace my past as part of myself. I think that’s why I can speak and share my story now—something I never imagined I could share in public when I was still in Gihembe.

You now live in New York. In what ways do you keep your Bagogwe Tutsi culture alive?

It is not easy. I am the one and only person from the Bagogwe tribe who lives in New York City. I just read and talk to my friends and family on phone, and sometimes go attend weddings of the few Bagogwe families that have resettled in America from refugee camps in Rwanda.

Buy Now: bookshop.org

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

>> Next: What It Means to Be American