As I slide through the lace-curtained door, my glasses instantly steam up. The last thing I perceive before temporary blindness hits: Every table is occupied.

Merde! Did I book the wrong day in my faulty French? As the fog clears, I see a blond woman headed in my direction. “Come,” she says, easing my anxiety. There is no need to identify myself. Owner Arlette Hugon has me pegged as the only solo stranger lunching today.

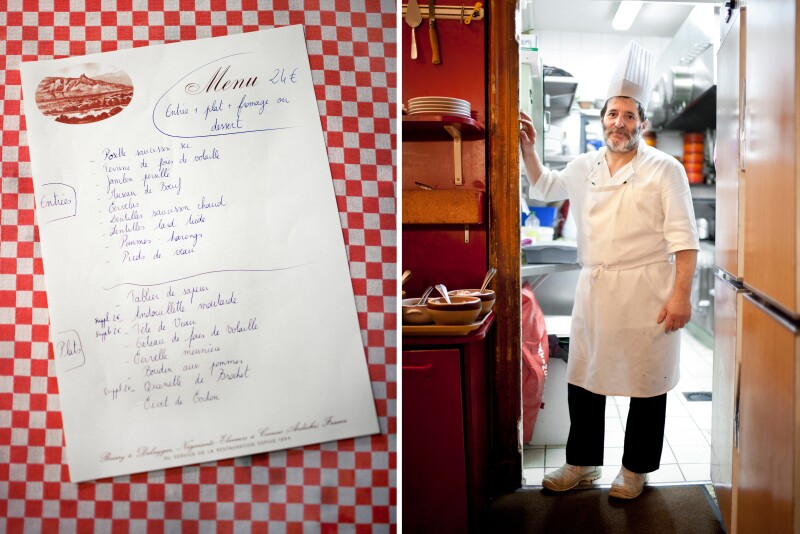

I’m in Lyon, France’s culinary mecca, home to nearly half a million people and almost 2,000 restaurants—including 11 with Michelin stars. But it’s not this Michelin constellation that interests me; I have come to eat in the down-to-earth establishments: bouchons lyonnais. Madame Hugon directs me to the empty seat at a table already occupied by three diners spooning veal sweetbreads from a big enameled pot in the middle of the red-and-white-checked tablecloth.

“Bonjour!” they greet me.

“Thank you for sharing your table,” I blurt in French, reeling a bit from the surprising seating arrangement.

“Oh, it’s a necessity here. Completely normal!” the man to my left answers as he pours red wine into my glass from a pot lyonnais, the classic thick-bottomed bottle for serving house wines. Chez Hugon is so small—with just 30 seats—and so popular that everyone shares tables. Like many of Lyon’s most beloved bouchons, Chez Hugon is tucked into a narrow side street near the opera house on the Presqu’île, a half-mile-wide inland peninsula carved by the confluence of the Rhône and Saône Rivers. And, like most bouchons, the restaurant specializes in homey dishes made with pork, organ meats, and other humble cuts, served in a timeworn setting that could most kindly be called “eclectic.”

I’ve come here to discover how these tiny, often family-run restaurants thrive in such a haven of high cuisine. What is it about bouchons that so captures the spirit—not to mention the taste buds—of Lyon?

My tablemates introduce themselves. To my left, there’s Yves; across from us, a married couple, Bernadette and Pierre. They all rendezvous here once a month for lunch. Madame Hugon lays a handwritten menu on the table and my companions chime in. We decide I should start with a traditional dish, pommes harengs, herring with potatoes.

For a main course, they advise the boudin aux pommes, blood sausage with apples. “It’s the best in Lyon,” Pierre asserts. Yves calls out to Madame Hugon and gives her my order, adding a pot lyonnais of Beaujolais wine. I attempt to speak French, and my new friends attempt to speak English. I tell them I’m from California, and Bernadette relates that her son spent a semester of college there, where he bought “the most beautiful of American cars—the Mooostaaahng.” My herring arrives, a lightly smoked fillet served over chunks of decadently silky potatoes.

“We should stop talking so she can eat,” Yves proclaims. “Five minutes of silence!” This lasts about 30 seconds, until my companions’ dessert and cheese orders appear. “You know, the EU is making us cook all of our cheeses now,” Pierre says, glowering as he cuts into a round of unctuous Saint Marcellin, a local cheese that is a staple at bouchons. “It’s the northern countries. They are used to cooking their cheese, so they think all the milk should be pasteurized.”

My boudin arrives. The platter holds an entire black sausage that sits atop apples caramelized with honey and onions. The sausage is light and creamy, almost mousse-like, a perfect savory counterpoint to the rich sweetness of the apples. It’s enough to feed two people easily, but I nearly polish it off. Madame Hugon passes by and reveals that the secret ingredient in the boudin is spinach. “Do you make the sausage yourself?” I inquire.

“No, under EU rules, we aren’t allowed,” she replies. I get the feeling that the Lyonnais might like to pack up their fabulous, bacteria-laden cheese, grab their homemade sausages, and secede from the European Union.

Yves downs a final sip of espresso and checks his watch. It’s 2:15. “Well, we’d better be getting back to work,” he says, then informs me that he’s paying for my wine. “It is my pleasure,” he insists as I protest.

This is not the first gesture of kindness I have experienced since arriving in Lyon a week ago. On my way from the airport, I had planned to take the metro but was stymied because the ticket machine spat out every credit card I fed it. Since the only other option was paying with coins, I asked a young woman pushing a stroller if she had change for a five-euro note. “No,” she said, “but I will buy your ticket!” She waved off my efforts to get her address so I could send reimbursement.

Most bouchons are located on the peninsula between the Rhone and Saone River.

Photo by Paolo Woods

After settling into my apartment on the Presqu’île that first day, I headed to Café des Fédérations, where the proprietor, Yves Rivoiron, set the tone for the conviviality I would encounter throughout my culinary quest. He knew I was a writer because I had asked in advance to talk with him after lunch. But when I arrived, he had other plans. “We’ll eat together,” he said, motioning to a booth. “My brother, Michel, is going to join us—he always has lunch here. That way you can taste what we order, too.”

Yves is in his early 50s, with cropped hair, stylish red-and-black glasses, and the slightly plump figure of a typical well-fed Lyonnais. “You must have wine,” he told me, filling my glass from a pot, ignoring my attempts to plead jet lag. “What would you like? I don’t have written menus,” he said, before rattling off a list of bouchon classics: quenelle de brochet (pike fish dumplings), saucisson au vin (sausage cooked in wine), poulet au vinaigre (chicken cooked with wine vinegar). Most dishes would be instantly recognizable to locals, because culinary traditions here stretch back to the 16th century. Bouchons are believed to have evolved as stops on the relais de poste, a mail-delivery system similar to the Pony Express. The name likely comes from bundles of straw—bouchons—used to groom horses. We can all give thanks that those French horsemen ate better than Pony Express riders.

A waitress brought the house appetizers—platters of sliced sausages, beet salad, and lentils with little cubes of cervelas sausage in a garlicky mayonnaise dressing. These starters could be a meal in themselves, but I opted for civet de joues de porc as my main dish. What appeared was a brimming pot of pork-cheek stew. The gargantuan portions are reminders of Lyon’s three centuries—mid-16th to mid-19th—as a center for silk production. Bouchons evolved to provide the nourish- ment needed to keep weavers at their looms for 18 hours a day. After our food arrived, Yves simultaneously talked with me, teased two cocky waitresses (“You’ll break your camera!” one cautioned when I asked to take a picture of her boss), joked with departing guests, and fended off his older brother’s gibes, all while digging into a plate of tablier de sapeur— literally, “fireman’s apron”—a thin expanse of breaded and fried tripe.

“Bouchons aren’t uptight like the grand restaurants. You can laugh here,” Yves explained, demonstrating with a hearty “Ha, ha!” “But at other restaurants”—he snapped his mouth shut, mimicking the atmosphere at more formal establishments by pursing his lips and glancing around like a cowed child afraid to misbehave. “In bouchons there is a mixture of classes,” Yves continued. “People talk with their neighbors. People need that.”

“So it’s OK to talk to people at other tables?” I asked.

“It’s not just OK, it is required,” Yves replied.

As a bouchon owner, Yves also has requirements. “For a proper bouchon, you have to have le vin en pot and checkered tablecloths,” he said. “You have to feel age, the past—the true past—not a fabricated past, not the ‘new past.’ ” Yves pointed out the curiosities that make up Café des Fédérations’ interior. Sausages dangled from the ceiling and a collection of ceramic pigs congregated on the back bar. Clusters of framed photos, yellowed newspaper clippings, and decades-old sports posters blanketed the walls. “But the most important thing,” he added, “is you have to like people.”

Yves’s brother Michel chimed in. “You have to have charisma. Yves wasn’t so outgoing at the start. He’s evolved!” Yves rolled his eyes.

“Have you two always battled with each other?” I asked.

“Yes!” they both exclaimed, agreeing for once. “We even live on different rivers,” Michel said, sketching the Saône, where Yves resides, and his Rhône on the white paper topping our tablecloth. “He lives on a sewer!” Michel declared, jabbing the Saône with his finger. Yves laughed it off. I laughed too; the Saône didn’t strike me as sewer-like. In fact, I’d seen swans floating on it.

Toward the end of our meal, Yves’s 22-year-old son, Julien, wandered in. He cooked at Christian Têtedoie, one of Lyon’s Michelin-starred restaurants, before taking a new job at Sketch in London. “Maybe he will take over someday?” I asked. “Well, I have only been here 13 years,” Yves replied. “The previous proprietor was here 25 years, and the one before him, 25 years, too.”

Photo by Paolo Woods

Since it’s physically impossible to eat more than one massive bouchon meal per day, I gathered ingredients for more modest meals at Lyon’s markets, where I continued to experience the city’s alchemy of food and kindness.

The indoor market, Les Halles de Lyon Paul Bocuse, is a tribute to the city’s gastronomic icon, 86-year-old Paul Bocuse, named Chef of the Century by the Culinary Institute of America for such achievements as holding three Michelin stars for 47 years. The market is also a temple to the bounty that feeds Lyonnais bellies. From northeast of the city come the famous Bresse chickens (shockingly granted an exception by the EU to be sold with their feathered heads intact) and Dombes pike fish, raised in ponds dug by monks during the Middle Ages; from the north, Charolais beef and Beaujolais wines; from the south, fruits, vegetables, and wines of the Rhône Valley; and from the west, pork for sausages like the rosette and the Jésus, the latter named for its resemblance to a babe wrapped in swaddling clothes. At Sève, an elegant chocolate and pastry stand, when I picked out six macarons, the clerk tucked two extras into the box. “The salted caramel are the best!” he exclaimed. “You must try them!”

As I explored the outdoor Quai Saint-Antoine Market, a favorite haunt for local chefs along the banks of the Saône, a florist noticed me taking a photo and struck a mock dramatic pose, raising a bouquet overhead. A man selling bright crescents of sliced pumpkin called out, “Ten euros per photo!” as he grinned for my camera. A baker asked where I was from and, as most Lyonnais did, graciously complimented my French. In fact, people struck up conversations everywhere—on buses, in front of shop windows, walking down the street. My time in Lyon was liberally seasoned with encounters you’d expect in a small town, not France’s third-largest metropolis. It seemed as though the friendly spirit nurtured in bouchons spilled out onto the streets of Lyon, making its citizens outgoing, chatty, and quick to help a traveler.

The ingredients I’d seen at the markets got gourmet treatment at Le Garet, where I savored my next bouchon meal. The owner, Emmanuel Ferra, has worked in one- , two- , and three-star kitchens—including Bocuse’s flagship restaurant, L’Auberge du Pont de Collonges—but he found his home at Le Garet.

“I have a bouchon because I need more of, how you say, generosity,” Emmanuel explained. “I want the time to speak with my guests and less pressure in my job. My food is the same as me: very generous, very simple.”

Despite his claims of simplicity, Emmanuel turns out nuanced renditions of classics such as tête de veau (calf’s head), as well as daily specials—perfect lamb chops or fork-tender boeuf à la bordelaise—that reflect his culinary skill. But, like most bouchon dishes I saw, they’re served without a thought toward presentation. There’s no garnish, no artful arrangement of ingredients. It’s all very generous, very simple.

Emmanuel, who is 40, with a stubbly beard, hustled back and forth between the kitchen and a dining room that is plastered with paintings, rugby jerseys, photos, and caricatures of past guests. These cartoons were all drawn with red noses, the trademark of Gnafron, a wine-loving puppet in Lyon’s long-running version of a Punch and Judy show, who also frequently appears in bouchons. “Ah! The decor is very special,” Emmanuel said. “We change nothing! Over the years, different bosses added another decoration, and another decoration. For me, they are very special bric-a-brac.” Le Garet is more than 100 years old, and when I glanced around, it was easy to believe nothing has ever been touched. Or even straightened. The painting hanging drunkenly behind the bar could have been askew for generations.

Just as the decor of bouchons remains unchanged, the atmosphere is as inviting as ever. “We want it to be the same as it is at your house,” Emmanuel said. “When you enjoy a dish, you can say, ‘Oh, I want a little bit more. I can help myself.’ The kitchen of the bouchon is generous. Generous!”

When I ordered cassis sorbet with marc, the French version of grappa, for dessert, Emmanuel set the bottle of marc right on the table so I could pour on as much as I liked. “This restaurant is a big love affair between guests and me. That’s very, very important. It has to be from here,” he said, clasping his hand to his chest. “Without the heart, it is nothing.”

We probably have the Mères Lyonnaises to thank for creating the warmth that suffuses bouchons. These “Lyon mothers” started their own restaurants when the silk industry declined in the late 1800s and they could no longer work as cooks for bourgeois families. They set the tone for the city’s culinary scene, contributing recipes and, I suspect, lots of love.

While most chefs today are men, I felt I had encountered a true mère lyonnaise when I met Joséphine Giraud. To reach her small, out-of-the-way bouchon, A Ma Vigne, I ventured from my apartment on the Presqu’île and crossed the Rhône via the Pont de la Guillotière into a nondescript neighborhood of furniture stores and government offices. Madame Giraud is 87 years old (“Born on June 6. I’m a Gemini!” she told me), but she zipped around the restaurant’s two petite rooms like someone half her age, taking orders, delivering desserts, chatting with guests, and sharing recipes.

Her son, Patrick, splits duties with her. He has a shock of gray hair and a quiet sense of humor. When I asked if I might snap a few photos in the plain, low-ceilinged dining room, he cautioned, “Just don’t take pictures of the clients. It’s like a home for them, and they could be here with their mistresses, you know.” I ate lunch because that’s the only meal served at A Ma Vigne. (And forget about dining on weekends. Like many bouchons, it’s closed then.) I was pondering the list of traditional Lyonnais salads known as cochonnaille—one featured beef muzzle, another calf’s foot, and a third lentils—when Denise, the waitress, offered to make me a combination plate of all three.

Le Garet, a bouchon that exemplifies the quirky character of Lyon’s beloved restaurants.

Photos by Paolo Woods

The muzzle was not as daunting as it sounds; the combination of meat and chewy cartilage was pressed in a terrine, then sliced into thin pieces. The calf’s foot was a plate of small, almost crunchy gelatinous cubes dressed in mayonnaise, an acquired taste; and the lentils were delicious, tossed with bits of cervelas sausage. “Did you like it?” Madame Giraud appeared at my table, looking concerned at my half-eaten plate. “Yes, but I don’t want to eat too much, because I’ve ordered the steak frites,” I replied. She smiled and nodded. Her steak frites is said to be the best in Lyon. The steak arrived at the table sizzling on a white porcelain platter, swimming in a pool of brown butter. As Denise spooned the butter onto my plate, she offered: “If this isn’t enough steak, you can have more. Just ask.” When I told Madame Giraud that her crispy French fries were the best I’d ever eaten, she replied, “I come here at six-thirty every morning to peel the potatoes. I’ll show you!” She rushed back to the kitchen and returned with a potato and peeler to demonstrate her technique. She stripped the skin off with quick, sure strokes.

“How long have you been doing this?” I asked.

“It’s fifty years since I started the restaurant,” she replied. “Over time, I have served the grandparents, then the parents, the children, their little children. I adore my work.”

As I watched Madame Giraud attend to her customers, I understoodhow bouchons have survived over the centuries. It’s a deceptively simple formula: Kindness. Generosity. Good, basic food. Respect for the past. Love for what you do. On my way out of town, I’m reminded that the Lyonnais don’t limit these values to their bouchons. I’m on the street, waiting for an elevator down to the metro. When the elevator arrives and the doors open, I hesitate to get on. I don’t want to squeeze myself and my bulging suitcase in with a woman who must be nearly Madame Giraud’s age. But the woman motions me to get on, so I do. She asks where I’m from and (of course) compliments my French. We continue our conversation until we both get off at the same stop.

“Which way is the train station?” I ask. She doesn’t just tell me; she walks me all the way to the escalator leading to the station. As the escalator carries me upward, I look back and see that she’s waiting at the bottom to wave good-bye. She keeps waving until I reach the top. The moment summed up what I had experienced throughout my visit: The Lyonnais go out of their way to offer simple, generous acts that feed both the stomach and the soul.

Photographs by Paolo Woods.