In the Mongolian steppe, the first thing you notice is the silence.

It’s as all-encompassing as the landscape—an open stretch of green and brown plains set beneath seemingly endless blue skies.

Next, you feel as though you’ve entered another planet. Until you realize what’s really in front of you: one of the last true wildernesses on Earth.

It’s this intensity—the stillness of the land and its unspoiled nature—that initially inspired French photographer Frédéric Lagrange to visit western Mongolia in 2001.

Mongolia’s Tolbo Lake extends more than 8 miles across the country’s western Altai mountain range.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

Over the next 17 years, Lagrange made 13 separate, month-long trips to the country, traveling from the southern Gobi Desert to the northern Taiga Mountains and almost everywhere in between. What resulted was a striking photography book project, Mongolia, which tells the story of this fascinating country through photographs of its landscapes and the people who inhabit them.

Traditional coats known as “deel” have been sported among Mongol tribes for centuries. They are commonly worn with a large silk sash.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

Which is, to say, not many. Landlocked between Russia and China, Mongolia is considered the most sparsely populated country in the world. Its 605,000 square miles are shared by some 3 million people, nearly half of whom live in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar.

The country’s vast terrains have served as roaming grounds for nomadic populations since the rule of the Mongol Empire during the 13th and 14th centuries. Today, Mongolia’s nomadic people make up approximately 30 percent of the country’s population. But as the world continues to modernize with the spread of technology to even its most remote corners, Mongolia’s remaining nomads have become some of the world’s last living practitioners of this lifestyle.

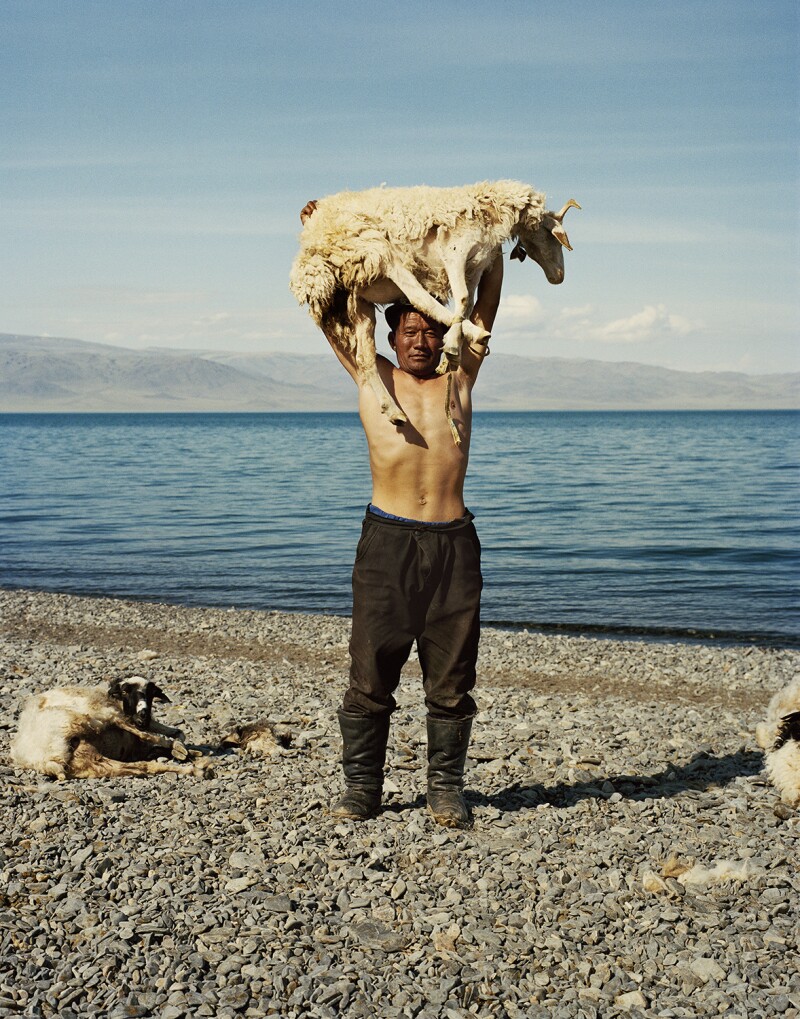

Mongolia’s nomadic herders tend to sheep, goats, camels, yaks, and horses just as their ancestors have for thousands of years.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

Lagrange first visited Mongolia in 2001, just over 10 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Inspired by his grandfather’s stories of being rescued by kind-hearted Mongol fighters as an imprisoned soldier during World War II, Lagrange had long held a fascination with the country and its people. According to the photographer, it was clear during his initial trip that the no-longer-regime-controlled nation was only just beginning to open up to outside influence and visitors. “Mongolian people had been very closed off to the rest of the world under Soviet rule, which was very evident during my visit,” he says. “There was very little technology and the country’s herding traditions were still widespread.”

Lagrange spent his first month-long trip to Mongolia mainly photographing the green, brown, and blue hues that decorated the landscapes in the western part of the country and, of course, the Mongolian people he crossed paths with along the way. But when he returned from the trip and looked at a map of Mongolia, he grasped just how little he’d actually seen of the country and felt compelled to explore more.

Lake Khövsgöl, located near Mongolia’s northwestern border with Russia, holds almost 70 percent of Mongolia’s fresh water. During winter, the lake’s surface freezes over completely.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

On each of his 12 Mongolian expeditions that followed, Lagrange and his local driver would seek out subjects based on word of mouth from the people they encountered. Nomadic tribes living in certain areas of the country would often have information about where other tribes might be located based on the time of year and specific weather conditions in each region, as herders and nomads dictate their movements according to their animals’ needs. What struck Lagrange about Mongolia’s nomadic people was not just their intense connection with nature—it was their comradarie toward one another as well.

In Mongolia, the key to successful nomadic existence seems to be that everybody’s contribution is considered crucial.

“You can travel for miles sometimes and not see any villages or communities,” Lagrange says. “But when you do, you’re immediately invited into the ger [a traditional Mongolian yurt] for warmth and food.”

The harsh realities of a nomadic life in Mongolia—extreme sandstorms during spring and -35°F temperatures during winter—mean that community and teamwork are central to survival. Within Mongolia’s nomadic communities, men, women, and able children are commonly expected to partake in responsibilities such as setting up camp, herding cattle, and preparing meals equally—gender roles aren’t rigid or clearly designated.

“In a country that’s so vast but with so few people, there’s a very big element of relying on others to survive,” Lagrange says. In Mongolia, the key to successful nomadic existence seems to be that everybody’s contribution is considered crucial.

A nomadic family in Mongolia’s Tsengel village gathers in their ger (portable tent) for a meal. The people in this area, near the Kazakhstan border, are known for practicing the ancient sport of eagle hunting.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

Today, traditional nomadic ways of life are rapidly changing across Mongolia. Herders can use cell phones to send messages they once had to travel miles to communicate. Changes in the climate have impacted long-standing cattle grazing rituals. Younger generations are moving away from the countryside and into the capital city, where education and employment opportunities are more attainable. “Part of this country’s distinct history might soon be gone for good,” Lagrange says. “I wanted to create a body of work that leaves a trace of this way of life before it goes away forever.”

The relationship between Mongolia’s nomads and the land they occupy is based on environmental knowledge and instincts that have been passed down throughout generations.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

Nearly 20 years after Lagrange’s first trip to Mongolia, his series of 185 portraits and landscape shots (both in color and black and white) will live permanently on the pages of a limited-edition photography book, available through Kickstarter beginning November 15, 2018. The body of work provides an intimate look at the evolving ways of nomadic life in the country—which, in some sense, the photographer participated in during each of his visits. “One of the things I found most interesting, which I’ve never found in any other place I’ve traveled to, is that you don’t see fences anywhere in Mongolia,” Lagrange says. “The country is fairly flat, except for the Altai mountain range in the west, which means you can practically cross the entire landscape without running into one fence that will stop you.

“There was an incredible sense of freedom traveling in Mongolia. You could look any way, in any direction, and say: Let’s go there.” He pauses.

“So, that’s what we did.”

In recent years, Mongolian winters have grown warmer and familiar weather patterns have altered, which has caused the country’s remaining nomads to change their centuries-old rituals.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

Buy Now: $280, bookshop.org

Products we write about are independently vetted and recommended by our editors. AFAR may earn a commission if you buy through our links, which helps support our independent publication.

>>Next: A Journey Through Mongolia in the Back of a Van Is What Road Trip Dreams Are Made Of