The bathhouse in the town of Paro was, according to my guide, a modest storefront unworthy of much description. Fine by me. As a blind guy, I don’t always care what the world looks like. What mattered most was the water inside.

My wife, Tracy, and I had landed in the Paro Valley for a week’s journey through Bhutan, the reclusive mountain kingdom tucked between China and India, near Tibet. Renowned for its Himalayan vistas, which would be wasted on me, Bhutan is also a destination for luxury travelers interested in the pursuit of “wellness.” The government famously measures the country’s success not by its economy but by its population’s happiness. When considering foreign investment, the kingdom considers how it might impact the nation’s Gross National Happiness. The Bhutanese must know a thing or two about feeling good. I was keen to find out.

Wellness isn’t exactly my default. My blindness is certainly a challenge, but perhaps more challenging is the armor of my ironic disposition. Humor has carried me through much, but I sometimes worry that this has been at the expense of a deeper spiritual well-being. Something healthier than a joke. I hoped to emerge fresh from the Paro bathhouse open to new experience and perhaps even to a new understanding of happiness itself.

The tiled room was private, as was my tub, a wooden trough like an open coffin that extended through the wall and into another room. In there, a fire crackled as two Bhutanese bath attendants prepared to cook me stupid. They dropped red-hot river stones one at a time into the water at their end of the tub, thus raising the temperature in mine. Each stone released a hiss of steam and a balm of minerals that our guide, Yountin, said would soothe my joints and, bonus, wash away any bad luck, or what he paradoxically called “bad merits.” I could ring an electronic bell on the wall to stop them or to demand more hellfire.

Buddhist monk Thinley Wangchuck in his dorm room at Tango Monastery, north of Thimphu.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

How peculiar to smell smoke and feel water at the same time. How contradictory to scrub yourself in a bath tinged with soot. I luxuriated in it. Fire and water. Earth and air. An appreciation of elemental things is, I would come to learn, fundamental to the Bhutanese point of view. A traditional bath steeps you in the richness of its modesty.

That is until, feeling around for a towel, I knocked down the wall between me and the workers. For a moment they stared at my naked honesty. Privacy was gone. Modesty was, too.

Doing yoga when you’re blind is like learning origami from an audiobook. A lot of directions, a lot of confusion. My wife is a yogi. I am the opposite.

About an hour and a quarter from Paro is Thimphu, the kingdom’s capital, home to approximately 100,000 people and no traffic lights. Cows and stray dogs wander the streets as if looking for parking, Tracy noted. Passing through, we climbed a winding mountain road to the first of three Six Senses resorts we would visit, each in a different region and elevation, each inviting its guests into a unique landscape where they can participate in a specific wellness experience. The resorts are the childhood dream of their owner, Dasho Sangay Wangchuck. A funny and loquacious entrepreneur, he dined with us on our first evening at a table crowded with plates of pomegranate salad, braised yak meat, and Bhutan’s national dish, ema datshi, or chili peppers with cheese. He had grown up in his father’s hotel, and as a child he had witnessed the impact Bhutan’s natural beauty and spiritual depth had on its occasional visitors. Later, as a young man attending university abroad, Dasho could appreciate even better Bhutan’s unique appeal. His is a country skirted by the tallest mountains in the world, protected for centuries from colonization or influence. His is a country that permits only a limited number of tourists and did not allow television until 1999. In some respects, it is a culture that is very new and very old, with little in between.

Perched on a mountain and surrounded by apple orchards, the Six Senses Thimphu resort is a monastery-inspired lodge referred to as the Palace in the Sky. An aerial motif touches everything. Clouds pattern carpets. The ceiling of its restaurant, Namkha, is hashed with beams chiseled in shapes that undulate like a cloud. A wall of windows brings the sky into each villa and simultaneously pushes guests out to the edge of the earth. In the main foyer, a painting of the medicine Buddha reminds visitors that they are here for health. There are no plastics. Even our toothbrushes will biodegrade. Housed in something so healthy, we would similarly tend to the betterment of our bodies. Maybe I’d find a box of functioning eyeballs on my nightstand.

The town of Paro stands on the banks of the river known as Paro Chhu in Dzongkha, Bhutan’s national language.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

Massage is not my thing. I spend too much time steered by people, grabbed, guided, or any number of other verbs that involve touch. The help is nice, but the guidance makes me feel as if I’m in a chronic state of correction. My wife and I, freshly unpacked in our gorgeous room in the sky, with its view of another breathtaking valley I couldn’t see, were about to receive our first Bhutanese tenderizing. When you think about it, massage is also a form of correction. You’re about to be pushed back into place, as it were. I bristled as they brought in the tables.

Our masseuses practiced a style called marma, which began not with hands or oil, as I had assumed, but with voice. A meditation. Tracy and I were invited to imagine the sky and smile at the sky. To breathe the air and smile at the air. Then flowers. Soil. Again and again we were encouraged to engage the world around us and to feel a gratitude that would relax our own physical being. As they chanted, each masseuse played a singing bowl and held it close to our ears until the note collapsed into smaller, cascading harmonics. The bowl was then placed on my stomach, sending its vibrations through my skin, moving its tone through my muscles and bones. A sound massage. In our daily lives, we forget that sound, being a vibration, is actually a form of touch. The ear is a finger. Through words and music, they managed to relax me into an hour and a half of elbows and fists, oil and unknotting bliss, that I would otherwise have resisted.

The next morning, Tracy and I met Dr. Tamhane, our Six Senses yogi and wellness consultant, in the prayer pavilion for yoga. Pavilion is misleading. It makes me think of trade shows. Rather, we had approached what Tracy described as a room of windows floating in a pond. The idea is to immerse you from above and below in light and sky.

Doing yoga when you’re blind is like learning origami from an audiobook. A lot of directions, a lot of confusion. My wife is a yogi. I am the opposite. Only once did Tracy try to teach me. We didn’t get past sitting. She said I even breathe ironically. This time, I promised myself, I would be sincere.

Some luxury resorts, such as Six Senses Bhutan, have multiple locations that put you at the center of the country’s natural beauty.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

“And now, moving into Cow Face Pose,” the good doctor said. “Breathe and reach.”

Everything I am, body and mind, kept getting in the way.

I was stiff and jokey, not relaxed and open like a cow’s mouth. Sometimes, as I tried to touch the mat with my fingertips, the doctor would give me glimpses of my wife for comparison.

“Good, Tracy,” he said at one point. “And now all the way, that’s right, nose to the mat.”

Jesus, these people. I can’t even sit cross-legged, but Tracy was folded like a napkin and chilling with her face on the ground. If that was Cow’s Mouth Pose, mine would be better called Toothless, Closed-mouthed Big Mac in Waiting.

“And finally, Wheel Pose, press up and arch your back,” the good doctor suggested, bringing our session to a close.

My back arched like a yardstick.

Yoga did not make me feel better. If anything, it confirmed for me that my body is a bag of paste and crowbars. The thought almost caused me to laugh. And for that, and so many other jokes, I felt toxic. Here I was, learning yoga amid ancient monasteries and dzongs (fortresses), but I couldn’t stop cracking wise. In meditation and silence, all I could hear was the shooting gallery of chatter in my head.

Then again, is that so bad? Irony is a muscle I have stretched and trained for my health, if not my survival. A laugh is the only cure for blindness I have known. The world as I bump through it just can’t hurt as much.

We met Dr. Tamhane again that afternoon. He affixed sensors to my forehead and chest and feet, wiring me into a laptop that would produce a diagnostic portrait of my biochemistry and organ health. But as the computer processed my data, I was confronted by the most obvious downside of tinkering with one’s wellness: What if he told me I wasn’t fine? Don’t ask what you don’t want to know. As we waited for my numbers, the worry tightened my chest, which made me worry that my anxiety about the results was tanking my data, live. I was caught in my own feedback loop. Finally the laptop spat out my score and, as he read it, Dr. Tamhane sighed, “Oh, wow.” From what I could hear, I would be dead in five minutes.

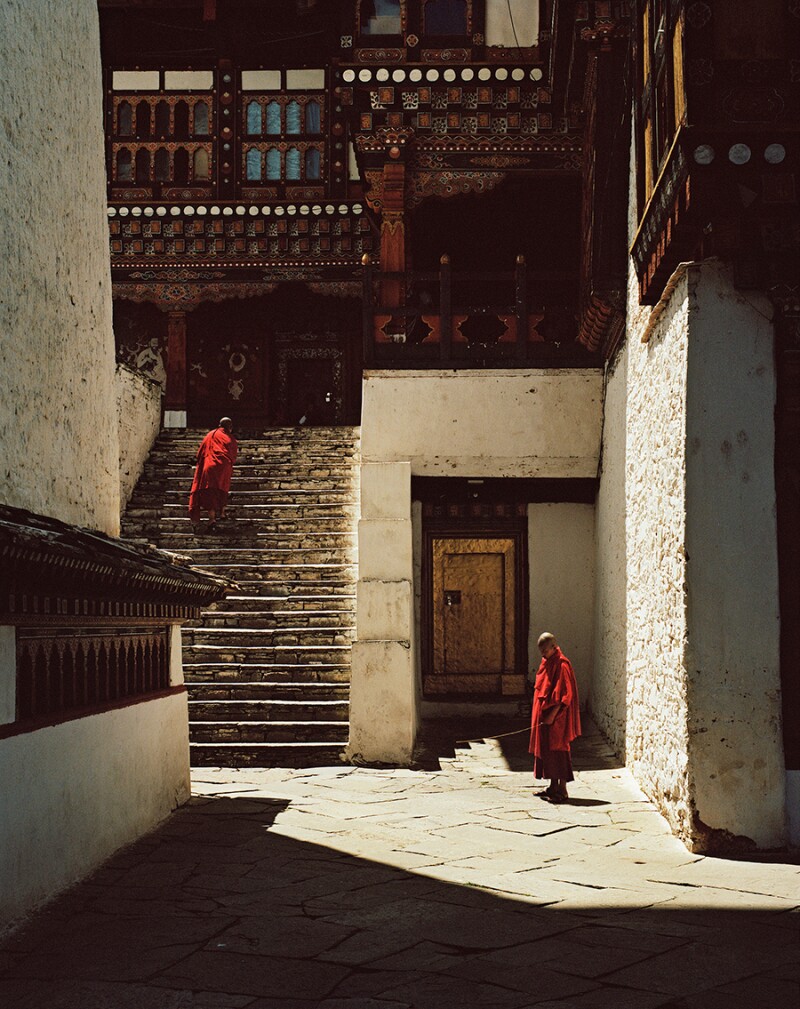

Rinpung Dzong is a large monastery located in the Paro District of Bhutan. The name translates as “the fortress on the heap of jewel.”

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

What I didn’t see was his smile. My cholesterol, blood pressure, oxygen levels, liver and kidney function, all of it generated an overall physical wellness score of 91 percent. He’d rarely seen one that high. He’d meant the good kind of wow. To this day, I feel like a 68, but, science.

Tracy and I strolled to dinner that evening under innumerable stars. She stopped and pointed into the darkness, puzzled.

“There’s a dog sleeping in a tree.”

That sounds like a pose I could do, I thought.

The four-hour road trip from Thimphu to Punakha takes you from the capital’s public square, where they hold Druk Super Star, a singing competition, to the north, past archery fields and the occasional nomadic yak herder, up, up winding cliff roads, ever higher, and finally, at 10,000 feet, across the Dochula Pass. The prospect of death is always with you. Driving, you will see countless prayer flags tied to bridges and railings, each a gesture to honor the deceased or a wish for safe passage. Yountin, our guide, helped Tracy and me tie our own prayer flags to a bridge as the snow fell on the pass. Given the heights, we prayed not to fall, too. You will also spot many stupas, the small Buddhist shrines that hold hundreds of tiny sculptures made by monks from a mixture of clay and the ashes of the dead, fashioning them together into something that resembles a child’s spinning top.

It seems that, in Bhutan, wellness comes from giving your cake away, not having it and eating it, too.

Everywhere you turn in Bhutan, it seems, something is there to remind you that luck, good and bad, is a force. You’d best take the proper precautions. Later in the week, we stopped at an incense factory where men rolled large coils of what felt like damp spaghetti. We dried a length on the dashboard heater in our car for days, and later burned it as an offering for good fortune. Incense is everywhere, the smell scrubbing the country of bad spirits. Prayer wheels abound equally, always whirring in the distance.

In a private home we visited for lunch, a local monk was at work. He gently took my hands and dipped my fingers into several bowls to let me feel the butter he was painting on a ritual cake that, from what I could feel, was half my size. This was a spiritual service for our host family. The offering would bring prosperity and more good luck. Smaller cakes would also be left on the roof for the crows to take to the gods. It seems that, in Bhutan, wellness comes from giving your cake away, not having it and eating it, too.

Six Senses Punakha is quite literally a flying farmhouse. Overlooking a warm valley cleaved by two rivers called the mother and the father, the resort’s main building is ingeniously engineered to hover over an expanse of rice paddies. Angled steps surprised me as I walked. Climbing the land around us was an entirely different collection of angled steps. These were the terraces on which farmers grew wheat and more rice. In walking the steps of our new stay, my feet were feeling a small likeness of the landscape around us.

Six Senses Bhutan allows visitors to personalize their experience with wellness treatments inspired by the area.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

The Punakha area is perhaps most famously known for its ubiquitous depictions of male genitalia. Punakha is where Drukpa Kunley, the Divine Madman, first arrived from Tibet in the 15th century with his brand of sexy, drunken, bacchanalian Buddhism, and his legacy persists! A road sign might replace an arrow with a penis. Phalluses frame archways and adorn everything from doors to keychains. In a small souvenir shop, Tracy placed a clay statue in my hands. It had veins and a smiley face. Resting on every shelf I touched was an object that seemed happy to see me. Some were hairy and woolen, some cast in bronze, eternally erect. It was like being surrounded by the enthusiasm of exclamation marks.

My focus was elsewhere. Chorten Ningpo is a Buddhist monastery about a two-and-a-half-hour hike from the Punakha farmhouse. Many tourists visit Bhutan specifically for a hike like this. Given the thin air and potential altitude sickness, choosing to hike is a serious commitment. So we drove, with Yountin at the wheel. Also, Tracy is afraid of heights. When Yountin parked the car on the cliff’s edge by the monastery gates, it made her scream. My wellness was intact. Blindness has advantages.

Yountin guided us among the 16th-century stone buildings and described to me their architecture and art, at one point guiding my fingers over an embossed gold depiction of a dragon. We were in the land of the Thunderdragon.

Yountin led us up a ladder into a room where three monks were in prayer with a bereaved woman. We sat quietly near the wall and listened to their rumbling incantations. They were the expressive, guttural tones I associate with throat singing. We’d heard other monks in other rooms before, including a group who rang bells and chanted, some holding skulls while others played flutes fashioned, I was told, from human thigh bones. To be present for so much ritual, from the prayer flags to the stupas to the cakes to these monks, made me realize how little of the sacred I had in my own life. All these experiences suggested the shape of a hole, but I had no idea what I would fit in there.

“Give me your hands,” Yountin whispered.

He quickly arranged my palms into a bowl and explained that the head monk was coming around. The man in the red robe had agreed to Yountin’s request that we also receive a blessing of holy water. I was instructed to drink most of it, which would cure whatever in me needed curing, then to press the remainder to my forehead for clarity of mind. Finally, a cure other than jokes.

Momo dumplings filled with cheese, served at the Six Senses Paro.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

The holy water arrived without a word, its trickle collecting in my cupped hands. Then, as I raised it to my lips, it dribbled through my fingers, gone. Goddamnit. My one shot at holy water and I fumble it. I didn’t feel I could ask for more, either. I’d be Bhutan’s Oliver Twist: “Please, sir, I want some more.” Maybe all my jokes were coming back to teach me a lesson. I pressed what moisture was left to my forehead and had the clarity of mind to know I’m an idiot.

Outside, we snacked on apples and listened to the sound of boys training to be monks. They were in a room on the second floor, its windows open, and, I was told, would occasionally peek their shaved heads out to get a look at us. I was heartened to hear them laugh as a few of them clubbed each other with their prayer books. Kids will be kids, even if they will grow up to be monks. Jokes before prayers. Maybe, in fact, there is a place for humor.

“I’m curious,” I said to Yountin, “do the monasteries have televisions?”

“Oh, for sure,” he said. “They love TV.”

“So what do monks like to watch? The Simpsons?”

“Soccer,” he said. “They love soccer. Big Manchester United fans. It’s the red uniforms. Monks wear red, too.”

After a week of considering my body and soul, and how to find wellness therein, it felt good to come back to Paro, where our journey had begun. Tucked in a forest at the end of a winding, rough mountain road, the Six Senses Paro resort is a series of stone buildings that complement their neighboring monastic ruins and sit atop a subterranean warren of massage and prayer rooms. One evening I sat outside and drank ara, a kind of sweet moonshine, and took a very temporary vow of silence as I listened to the stray dogs under the stars. They howled for something. We all do. Maybe soon they would try to sleep in their trees.

Tenzin Jamtsho is a member of the staff at Six Senses Thimphu, a monastery-inspired lodge referred to as the Palace in the Sky.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

On our last day we stopped to visit a monk at an astrology school. He would tell Tracy and me about our past incarnations, our present selves, and our future paths. We met him in a room that felt like it belonged to a community college professor. It was small and dark and pack-ratted with books and shelves. A yak hide covered the couch. I sat on it and waited as the monk took my birthday information from Yountin, who translated between us. When he was ready, the monk consulted several serious tomes and made some notations, calculating my past to find my fate. My thoughts turned to the past week. All this wellness, the stone baths and yoga and doctors and holy water, but what if the question of well-being is, in the end, a fixed proposition? Sure, less gluten and more mindfulness feel good, but what if they don’t, in the end, change the story of who you are?

The monk was ready. He had my answers. “In this life,” he told me, “you will have some problems with your senses. But you will travel. And although you will travel very far in this life . . . you are not looking for anything.”

It took me a moment to realize how true this is. As a blind man, I literally wander the globe and, like it or not, look for nothing. But in doing it, I am at my best. I am well. We think of being well as a thing to pursue, as a state of being to reach, like a destination. Like a country or a beautiful hotel. But it’s really more like water through your hands. A pleasure to have tried and fumbled. We can cry or we can laugh about it.

I wanted to say something about this to the monk. I wanted to take him outside and have a philosophical dialogue with him under a tree, or under a dog sleeping in a tree. I had questions about my happiness. I wanted to tell him something funny that happened along the way.

But his phone was vibrating on the desk. Its custom ring tone was a Buddhist chant. He was busy. He ushered us out, bowed a polite goodbye, and shut the door to answer his calling.

Six Sense Bhutan currently has three open locations in Paro, Thimphu, and Punakha, with two more set to open in 2019.

Photo by Frédéric Lagrange

How to Travel to Bhutan

Nestled in the Himalayas between China and India, Bhutan is a tiny kingdom known for its dramatic landscapes, sacred sites, and holistic approach to happiness and wellness. To protect its natural resources and ensure that travelers don’t overwhelm the country, tourism is tightly controlled. Inbound flights are limited, and travelers must pay special fees to obtain visas—a multistep process made easier with the help of a travel advisor or an outfitter. (You can find members of AFAR’s Travel Advisory Council here.) Travel companies such as GeoEx, MT Sobek, and Kensington Tours offer package and custom itineraries and help with some of the hassle.

Visas

American visitors need a visa to enter Bhutan. In order to get a visa, you must book a tour with a licensed guide or program operator. A visa costs $40 and visa clearance must be obtained in advance.

Spending minimum

Bhutan mandates that tourists spend approximately $200–$300 per person per day. The amount depends on the time of year and the number of people you’re traveling with, and includes accommodations, meals, transportation, and other activities.

Flights

Only two airlines—currently Drukair and Bhutan Airlines—fly into Paro Airport, Bhutan’s only international airport. Flights are routed through hubs including Bangkok, New Delhi, Singapore, and Kathmandu. Weather can delay flights for days at a time—it’s important to have your itinerary designed with a few days in your stopover city and to fly on an unrestricted ticket.

Other helpful information

Medical care in rural areas can be limited; supplementary medical evacuation and travel health insurance are encouraged. Some outfitters offer coverage through third-party travel insurance companies. Credit cards may be accepted in certain hotels and shops in larger cities, but ATMs are unreliable, so it’s best to exchange dollars for Bhutanese ngultrums, the national currency, before you leave home. Though not mandatory, updated vaccinations are strongly recommended. Check cdc.gov and travel.state.gov for a list of recommended vaccinations.

Wellness retreats

Wellness retreats are a popular way to unwind and experience the local culture; much like tour companies, they offer assistance throughout the planning process. Some luxury resorts have multiple locations, and most guests stay at several lodges during their trip.

Six Senses Bhutan puts you at the center of the country’s natural beauty and allows you to personalize your experience with treatments inspired by the area, which include hot stone baths and Bhutanese herbal scrubs. Six Senses currently has three locations, with the fourth opening in Gangtey in October and the fifth in Bumthang in early 2020. Amankora, a circuit of five luxury lodges, offers adventurous and wellness-centered itineraries accompanied by a private guide, starting from three nights.