I fell in love with Russian pies before I ever tasted one. As a sophomore in college, I was reading Chekhov’s story “The Siren” when I came across this line: “The kulebyaka should be appetizing, shameless in its nakedness, a temptation to sin.” What siren was this, that beckoned so wantonly? I had to find out. I soon discovered that kulebyaka is a multilayered fish pie, only one of the many glorious pies that characterize Russian cuisine. I also discovered that Russian literature is replete with references to pies, from Chekhovs, dripping butter like tears, to Gogols, a four-cornered kulebyaka luscious enough to make “a dead man’s mouth water.”

Russian pies come in all sorts of shapes and sizes, with a near-endless variety of fillings. Because they symbolize well-being, they’re considered celebratory, although talented cooks also make magic by enclosing leftovers in dough. The pinnacle of Russian pies might be the kurnik, a large domed creation that’s light-years away from a homey chicken potpie. Half a foot tall and layered with chicken, mushrooms, and rice, it’s traditional for weddings. Before the revolution, there was even Pie Day, the third day after the wedding ceremony, when brides were expected to show off their baking prowess and thereby demonstrate fitness for marriage.

A pie’s success—and magnificence—depends on the harmonious conjunction of several elements: filling, dough, shape, and cooking method.

A pie’s success—and magnificence—depends on the harmonious conjunction of several elements: filling, dough, shape, and cooking method. I could write a small book enumerating all the possible fillings and the inventiveness with which Russians use them, from a spare and simple pie stuffed with chopped cabbage and onions to a cholesterol-rich extravaganza layered inside with crêpelike blinchiki, farmer’s cheese, hard-boiled eggs, and butter. The diversity of fish pies alone is astounding, from a silken mousseline filling in a puff-pastry envelope to a sturdy bread crust wrapped around a whole zander. Sweet fillings include berries, stone fruits, and apples, not to mention farmer’s cheese and jam.

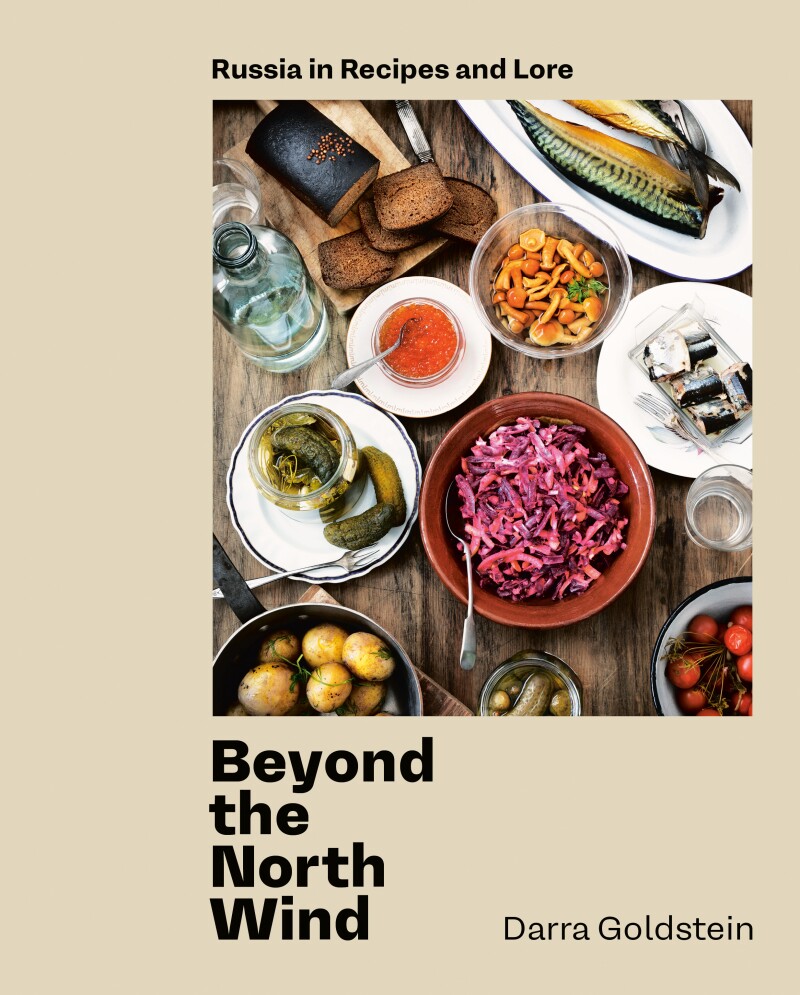

The cover of Goldstein’s latest cookbook, which was released in February 2020.

Cover courtesy Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House

Pie dough can be made from either rye or wheat flour or a mixture of the two and can range in texture from a quick, short dough made with sour cream to a yeast dough that’s either crusty and lean or soft and enriched. Flaky pastry and puff pastry can also be used. The art lies in choosing a dough that will complement the filling, both in flavor and texture. The proportion of dough to filling also varies considerably from pie to pie, and from region to region. In the Russian North, where fresh fish abounds, fish pies contain much more filling than crust; in Russia’s interior, the ratio is often reversed. The filling and dough determine the shape of the pie, whether it’s round, oval, triangular, square, rectangular, boat-shaped, or domed. Pies are baked open-faced, latticed, or enclosed, in shapes large and small. Small pies—pirozhki—are a genre unto themselves, within which many different styles appear. Though large Russian pies are always baked, small ones can also be pan fried or deep fried.

Even the most basic pirozhki are often sealed by means of decorative pleating that reveals the Russian love of ornamentation. Special-occasion pies are a marvel, their crusts covered with scraps of dough cut into leaves, flowers, and other organic or geometric forms to create a bas-relief. Inventive bakers sometimes use two different kinds of dough for decoration, making intricate patterns of white wheat and dark rye dough on the top of the pie. For a golden sheen, the crust is usually glazed with an egg wash before baking.

In the tsarist past, pies constituted a separate course at luxurious dinners, when they were served between the fish and the roast. In the nineteenth century, small pies also began to be offered as accompaniments to soup, and by the twentieth century, they’d become a fixture on the zakuska table as well. And of course, teatime is unthinkable without a sweet pie, a genuine expression of hospitality. As the Russian saying goes, “The beauty of a house lies not in its walls, but in its pies.”

Reprinted with permission from Beyond the North Wind: Russia in Recipes and Lore by Darra Goldstein, copyright © 2020. Published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Products we write about are independently vetted and recommended by our editors. We may earn a commission if you buy through our links.