The story of the subway is the story of the city, with all its energy and dysfunctions.

The New York subway is crowded and decrepit. Chunks of concrete fall from station ceilings with alarming regularity. Rats no longer just scurry along the tracks. They climb up sleeping passengers and drag pizza slices through stations. Then their videos go viral. Passengers suffer long, unexplained delays. Something always seems to be going wrong.

But the subway is also a marvel. It’s extraordinarily efficient at moving millions of passengers a day. When the first line opened in 1904, it was the most advanced in the world, and a source of enormous civic pride. Its express tracks were unique. The project was a bid to put New York on the same footing as London, Paris, and Berlin, a symbol of the young nation’s aspirations.

Overnight, the subway became an essential function, and an essential part of New Yorkers’ state of mind. It inspired dance tunes and movies. Duke Ellington made the A train famous. Nearly a century after the subway’s debut, whole Seinfeld episodes revolved around it.

The subway is also the great leveler, forcing New Yorkers and visitors of all classes and colors to mingle elbow to elbow. It’s mandatory that mayors be photographed on a train, even if they rarely ride the subway. To be a New Yorker is to take the train, to celebrate it, and to grumble or joke about it.

The history of the subway and the city are so intertwined that you can’t understand one fully without understanding the other.

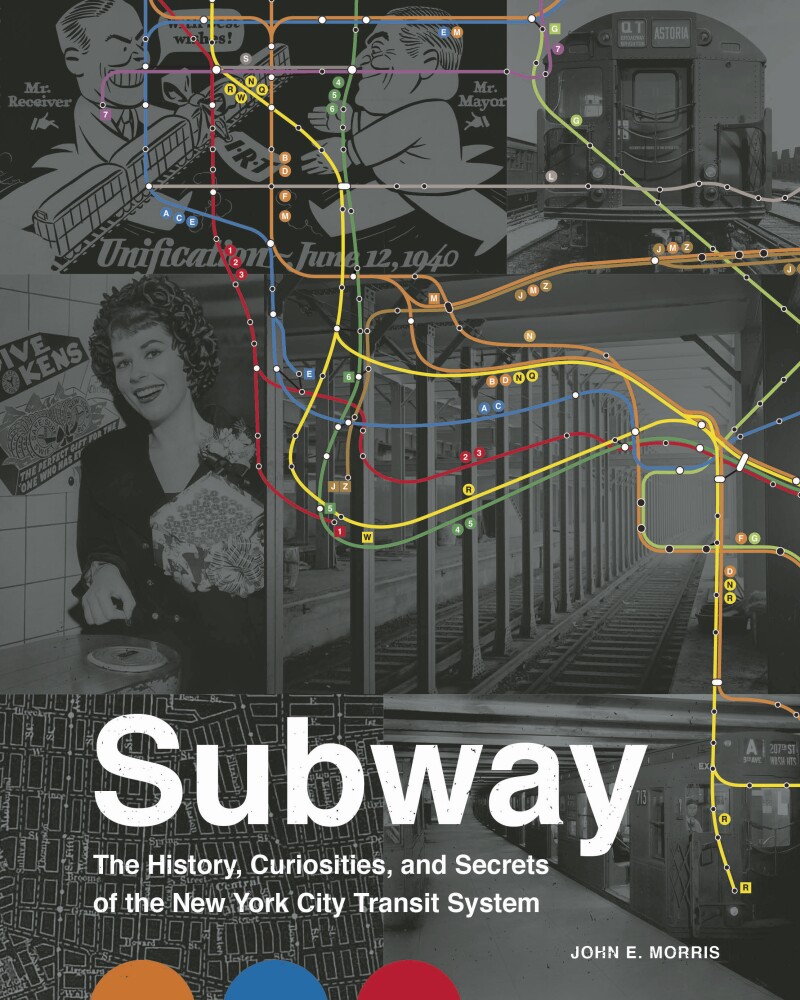

Image courtesy Black Dog & Leventhal

The city’s raucous politics have been at the center of the subway saga in every era. Battles over the subway’s creation in the 1800s pitted streetcar owners and public officials on the take against businessmen and social reformers who aspired to improve the city and society through better transit. William “Boss” Tweed, the city’s legendarily corrupt power broker in the mid-1800s, once planned to send a mob to tear down the first elevated line because it competed with his own transit ventures. In modern times, subway politics have too often been driven by photo opportunities. Mayors and governors repeatedly staged groundbreakings (cue the pickax, cue the jackhammer!) for a Second Avenue subway that didn’t materialize for decades.

The subway was a response to the needs of a city whose streets were clogged and whose slums were dangerously crowded. The city, in turn, was forever shaped by the subway—which neighborhoods got subway lines and which didn’t.

The five men most responsible for making the subway system a reality in the early 20th century are also a window onto the society and social forces of their time. Each is an archetypical American character.

The master contractor for the first line, John B. McDonald, was a no-nonsense, Irish-born immigrant who helped build some of the most difficult rail tunnels of his era. He was snubbed by August Belmont Jr., the wealthy banker and horse breeder who financed and controlled the first subway. But Belmont himself was just one generation further removed from Europe. His father was a German-Jewish immigrant who made a fortune in the 1830s, married into a prominent Protestant family, and assimilated into the city’s elite. The patrician bearing of the gifted chief engineer, William Barclay Parsons, reflected his descent from wealthy colonial landowners and his private school education in England.

The story of the subway is the story of the city, with all its energy and dysfunctions.

George McAneny, the reporter turned politician who brokered the major subway expansion in the 1910s, dedicated his life to civic causes: rooting out corruption, better public transit, city planning, and historical preservation. His frequent nemesis, John Hylan, the mayor who initiated the city-owned Independent Subway System (IND) in the 1920s, grew up dirt-poor on a farm in the Hudson Valley and put himself through law school while working on elevated trains in Brooklyn. The chip always remained on his shoulder.

The 10,000-odd workers who performed the hard labor, many of them fresh immigrants, likewise, were part of the American story.

Much of the subway story has been lost with time. Take Belmont and Parsons. They were prominent figures in their day, but there are no biographies of either in library catalogs or on Amazon.com. William Gibbs McAdoo, the lawyer who built the PATH subways to New Jersey, likewise, is largely forgotten, but this modest, able, likeable character had a colorful side and earned himself a chapter here.

Another chapter of the subway story is the what-ifs, the unfulfilled plans for new lines crisscrossing Manhattan and others spreading to the far corners of the outer boroughs. What would Staten Island be like now if it had been linked to Brooklyn by a much-promised subway tunnel across the Verrazzano Narrows? Would Downtown Williamsburg be a cluster of high-rise apartments or office towers if a 1929 plan had come to pass for two lines from Manhattan to intersect at a massive junction there?

Beyond the politics, personalities, and urban history, the subway is also a feast for trivia lovers. Did you know that tunnel light bulbs have reverse threads so they won’t be stolen? Or that old subway car shells dumped off the Atlantic seaboard are home to large schools of fish? Or that the director of The French Connection bribed a transit official to film a train hijacking on a real train running on regular tracks?

For those who love the city, the subway isn’t just infrastructure or a way to get to work. It’s a New York experience. In what other city could you hear a perturbed conductor bark, “Now listen up, folks!” and threaten to take the train out of service if passengers don’t remove the belongings obstructing the doors? (“Yeah. Right. He’s going to take the train out of service.” You can read the minds of your fellow passengers in such situations.)

Like the city, the subway frequently makes you laugh when it doesn’t make you want to scream. It is awe-inspiring when it isn’t exasperating.

Reprinted with permission from Subway: The History, Curiosities, and Secrets of The New York City Transit System by John Morris. Subway is published by Black Dog & Leventhal and is on sale October 6, 2020.

Buy Now: $30, amazon.com

Products we write about are independently vetted and recommended by our editors. AFAR may earn a commission if you buy through our links, which helps support our independent publication.

>>Next: Is This the Most Transcendent Way to Explore New York City?