Name: Fabrizia Lanza

Age: 49

Hometown: Palermo, Italy

Occupaton: Formerly an art historian in northern Italy, Fabrizia returned to her native Palermo to run a cooking school started by her late mother, Anna Tasca Lanza. The school is housed in Regaleali, an estate in rural Sicily owned by Fabrizia’s family since 1830. Fabrizia has also made several documentary films about the festivals and disappearing food rituals on the island.

What I love about Palermo is what we call promisquità—the way everything is mixed together indiscriminately. You have beautiful palaces next to alleys filled with rubbish, vivid colors and terrible smells, incredible gardens and grimy buildings. I don’t like tidy cities. Palermo is a fascinating place because it’s very ugly and very beautiful at once.

Take Camastra, my grandparents’ villa, where I was married. It was built in 1555, and it has lavish fountains and gardens. Most of Palermo was destroyed in World War II, and so these rare villas are surrounded on all sides by unattractive apartment buildings.

We have many beautiful churches and monuments, but what’s most alive in Palermo is the food. Palermo has a big corridor of outdoor markets, all with different names, and all very old. I go to the Ballarò market. These little carts arrive with old men selling exquisite vegetables—one has five plants of special rosemary or a particular basil, another sells only onions and garlic. It’s an ancient micro-economy—it’s amazing that it still exists.

The most important religious event of the year, the Festino, is celebrated in July with a feast in the streets. The holiday honors Santa Rosalia, the patron saint of Palermo, who is said to have saved the city from the Black Death plague in 1624. On that day, you eat babbaluci, which are wonderful little snails.

Cooks start off early in the morning peeling garlic and frying it in oil in huge pots. My house is right on top of the celebration, so the smell wakes me up. They start washing enormous bags of snails, and it’s like the sound of maracas. They pile them in huge dishes in the middle of the road—enough to feed 5,000— and pour seasoning on top: garlic, oil, parsley, salt, and pepper. Men queue up to fill paper cones with the snails and eat them in the street. They also make candy brittle in the street. Enormous men with two big knives twirl the brittle on a marble surface covered with oil so it won’t stick. This sort of technique is changing, because in the kitchens they have to use stainless steel equipment for health reasons, but the old recipes need marble, which helps cool down the ingredients in a certain way. You can’t pour syrup on a steel surface!

For the festival of Santa Lucia, in December, Palermitanos don’t eat anything with flour, but we boil wheat with sugar for a dish called cuccìa. The story goes that Saint Lucy saved the city from famine: A ship full of grain arrived mysteriously in the harbor, and the inhabitants were so hungry they didn’t have time to make flour. So they ate the grain whole.

I’m very interested in the old cuisine. We have something from all the people who have conquered us over the centuries. Some dishes are a little Arab, and French cuisine was in fashion at the beginning of the 19th century after Maria Carolina of Austria and Ferdinando di Borbone ran away from Napoleon and arrived in Palermo with their whole court. I like my cooking school to be a point of reference for traditional cooking in Sicily, from the ingredients—wild fruits and vegetables that are disappearing—to the way of preparing things. But it’s not a museum. We eat it. It’s alive.

See all of Fabrizia’s favorite places in Palermo:

Piazza San Francesco

Piazza San Francesco

This central square is famous for carts that serve Sicilian antipasti in front of the Oratorio di San Lorenzo, which has amazing 18th-century sculptures, perhaps the most extravagant art Sicily produced at the time.

Cappella Palatina

Cappella Palatina

Within the Palace of the Normans, there’s a chapel of the kings. “It’s sumptuous,” Fabrizia says, “all covered with mosaics. It’s like getting inside a golden box of jewelry.”

Mercato di Ballarò

Mercato di Ballar

People line up at seven or eight in the morning to order a big dish of soup made with tripe and intestines. You can get panelle (pancakes made from chickpeas) hot from the vendor. They also sell the most famous panino—spleen stuffed in a bun, which you eat either ‘married,’ with ricotta, or ‘not married,’ which is pure.

Via dei Biscottari

Via dei Biscottari

In the area of the Norman palace, near the market, there are still some little medieval botteghe (shops) below the level of the palace. Via dei Biscottari is where they used to make the pastries and cookies for the king. There is one shop I love to visit where they still make the shells for cannoli by hand. Sicilians love cannoli, of course, filled with fresh ricotta. We have an intense sweet tooth.

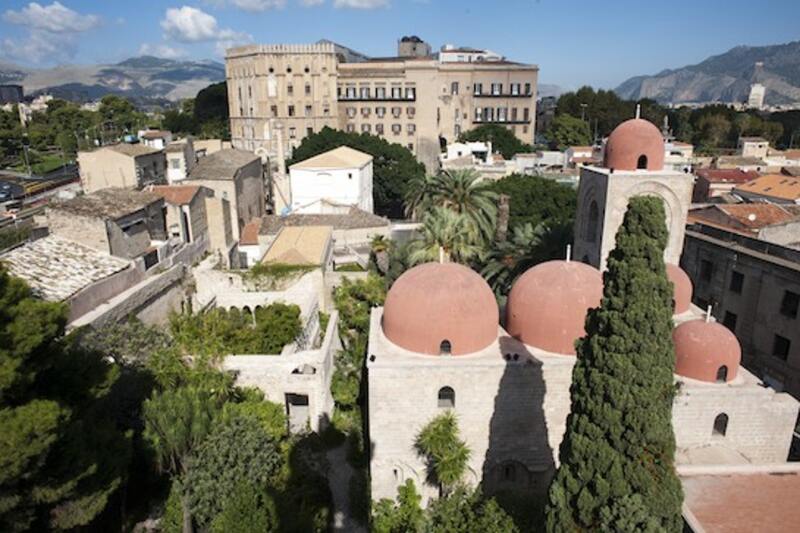

Chiostro di San Giovanni Degli Eremiti

Chiostro di San Giovanni Degli Eremiti

This 12th-century Norman church [St. John of the Hermits] has five Arab-inspired red domes. It’s a narrow little church with a garden filled with jasmine and succulents— a very peaceful place.

Palazzo Abatellis

Palazzo Abatellis

Palermo’s art museum, which houses medieval and modern works, is around the corner from the Mura delle Cattive (Wall of Widows). It’s in a well-preserved palace of the 15th-century Gothic Catalan epoch—we belonged to Spain at the time—and it was restored by Carlo Scarpa, one of the best Italian architects and designers, in 1953.

Kursaal Kalhesa Restaurant

Kursaal Kalhesa Restaurant

A restaurant built within Palermo’s ancient walls, where chariots were once housed. Under these enormous vaults there is a library, a garden, and a bar—it’s a fantastic place for drinks.

Teatro Massimo

Teatro Massimo

Palermo’s opera house, built in the 19th century and inspired by ancient Greek ruins in Sicily, is the largest in Italy and the third largest in Europe. You can catch Rigoletto, La Traviata—I love all of Verdi and Puccini; I’m Sicilian.

>> Read Next: The AFAR Guide to Italy