→ Order now: $17, bookshop.org

Jane Billinghurst first started working with legendary German forester and “tree whisperer” Peter Wohlleben in 2015. She was the editor and translator of his best-selling book, The Hidden Life of Trees (Greystone Books, 2016), which fundamentally changed the way many people—including Billinghurst—think about forests.

Combining their forces more deliberately this time, the pair coauthored a new book, Forest Walking: Discovering the Trees and Woodlands of North America (Greystone Books, 2022), which blends Wohlleben’s professional and scientific expertise with Billinghurst’s awe and wonder as a nature lover and master gardener. Billinghurst shares how to walk, hike, and wander with more attention—and intention.

What was a walk in the woods like before you and Peter started working together?

I live in Washington State, and I belong to a hiking club. We’d go out every week in the forest, and the idea was always to get from point A to point B. I mean, obviously, [we wanted] to enjoy the surroundings and be out in a wonderful forest, but mostly we wanted to get a workout. And I thought that was great. Working with Peter, I thought: Wait a minute, there’s a lot going on out here!

I learned that the forest is so much more than a landscape to walk through. It’s a place where life is happening all the time, sometimes very gradually and sometimes on a minute scale. I discovered that if I slowed down, I could catch glimpses of a complex world I had never noticed before. Over time, I have discovered I still like to get from point A to point B, but now I hike more slowly, which gives me time to scan my surroundings.

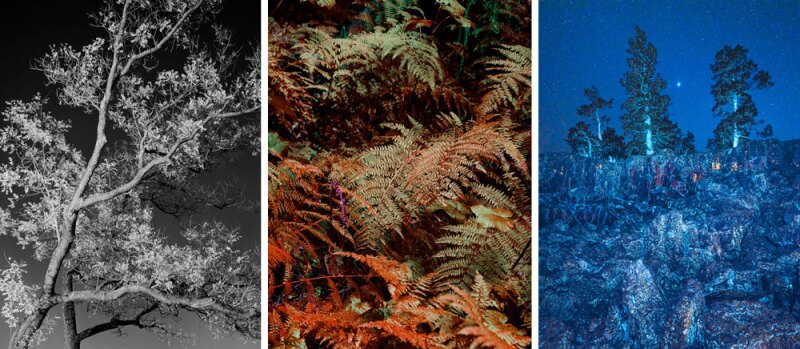

From left to right: an ash tree in Prospect Park, Brooklyn, a lady fern in Nelson, B.C., and a ponderosa pine in El Malpais National Monument, New Mexico

Photos by Daniel Ballesteros, Brendan George Ko, Cody Cobb

What do you mean by “scan”?

I realized that if I kept a slow, steady pace, constantly looking to either side of the trail, my eyes would begin to pick out what I was looking for. Now, as I’m walking, I look up and down and turn my head side to side. I’m trying to take in everything that I can. I usually have a particular focus for that day, because if you focus on everything, you’re never going to move off a single spot—there’s just so much to see.

One day my focus might be fungi, another day it might be lichens, another day it might be frogs. It might change during the hike. Once, in Silver Lake Park, up near the Canadian border, I was strolling from the campground when I realized there were slime molds everywhere. I had set out with no particular goal in mind, but slime molds soon became the focus of that hike.

Most slime molds are neither slimy nor moldy. They like moisture and shade, and they help recycle nutrients in the forest. They move to find food, and when they are ready to reproduce, some of them develop delicate, tubelike fruiting bodies on stalks. Some are very small—a collection of fruiting bodies might not be much larger than a quarter. The fruiting bodies I found at Silver Lake were white tubes on black stalks at about eye height on a dead trunk. Every time I turned a corner, there was another slime mold. It was fascinating. Before I worked with Peter and slowed down, I had never noticed a slime mold in my life.

Bald cypress adorned with Spanish moss form mysterious silhouettes at Texas’s Caddo Lake State Park.

Photo by Cody Cobb

When you’re noticing those details, what are you looking for? Or contemplating?

Let’s take the case of a nurse log. That’s when a tree falls in the forest, and it lies there to rot. Peter talks about how this is the process of the forest regenerating itself. This is the forest creating a closed cycle, so that all the nutrients that are bound up in the tree go back into the soil to feed the next generation of trees and other organisms.

To do that, you’ve got all these little critters that are busy breaking down that nurse log into its components. You’ll have mites and beetles and ants, and during certain times of the year, woodpeckers, because there are a lot of [insects] for them to eat. You can see where the bark has disappeared. You can see where the log has become mushy—as the components get smaller and smaller, those little critters are taking them down into the soil where the carbon is sequestered. You’re watching a whole cycle happen right there in front of you.

Another thing that fascinated me was how much you can learn about history by looking at what’s going on in the forest. If you’re in the northeastern United States, you find all these stone walls. That tells you that in the past, these may have been fields. People had cleared the land, either because the wood was valuable or because they wanted to farm. So you’ve got a sense of a lost history that the forest is almost protecting and conserving—and you can go find it. You begin to understand that you’re not the first person to come through this forest; it has been many things to many different people over time. It’s a dynamic system.

From left to right: bristlecone pine at Inyo National Forest, California, and a view of the forest-scape at Snoqualmie National Forest

Photos by Beth Moon, Cody Cobb

Which forests are you most fascinated by?

I learned about some interesting woods while writing this book. For instance, there’s a patch of Douglas firs in West Texas, and they’re there because of the Ice Age. The ice came down and covered the northernmost part of North America, and as it did, it pushed trees down the continent. As the ice receded, the trees migrated back up. But in some unexpected places, like right on the border between Texas and Mexico, some of these fir trees got left behind and are still growing there. It’s impossible to see that and not think about geological time; trees are living in such a different time frame and in such a different way than we are. And yet they affect us, and we affect them.

How has that changed your daily relationship with trees?

I like woods that are familiar to me and have a connection with my own life. I think I understand those woods better. I live right next to the Anacortes Community Forest Lands, nearly 3,000 acres of forest, wetlands, and rocky climbs protected by the city of Anacortes [82 miles north of Seattle] in partnership with the Skagit Land Trust. It’s fascinating to observe the changes, season by season, even day by day or from morning to night. On my regular walks, I check on the beaver dams, watch the trees steam when the sun comes out after a heavy rain, look for barred owls staring down at me, and listen for pileated woodpeckers. It’s also cool that [we can find forest] right where many of us live. You don’t have to travel far to find amazing things to see.

>> Next: 6 Ways to Support Rewilding Projects Around the World