When I was an architecture student at the University of Virginia (UVA), Thomas Jefferson was an integral figure in my undergraduate studies. I was required to learn about his designs for the Academical Village at the university as well as for Monticello, his 5,000-acre hilltop residence and former plantation. However, my greatest lesson on “TJ” came not from examining the Jefferson architectural style or his renowned writings, but from a required course field trip to Monticello 25 years ago. Back then, Jefferson’s achievements, ideals, and family history dominated the “guide speak,” brochures, and exhibits at Monticello, but as Monticello prepares to celebrate its 100th anniversary as a historic site, today’s narratives tell a much more inclusive story.

During my college years, there was considerable public discourse about the nature of Jefferson’s relationship with Sally Hemings, an enslaved young woman with whom Jefferson fathered six children. Yet my first tour of Monticello only briefly touched on their relationship—or the lives of enslaved people in general. Instead, it focused heavily on the home’s Palladian architecture, Jefferson’s meticulous record keeping, his love of horticulture, and his extensive book collection, which housed one of the largest libraries on architecture in the United States during his time. The tour also presented an idealized view of the third U.S. president, with little acknowledgment of his moral contradictions, such as being a staunch defender of liberty while owning hundreds of enslaved people.

Toward the end of that first tour, I visited the exterior gardens and Mulberry Row, the principal place of work and domestic life for enslaved people, free workers, and indentured servants. I remember spending several moments in contemplation at Mulberry Row, imagining the perils of being forced to work at Monticello and wondering about the names and faces of the people who lived and worked there. I left Monticello feeling that an important piece of its story was missing.

I was quite surprised by how drastically the narratives had changed when I revisited Monticello in 2022 during the national launch of Discover Black Cville, a community-led initiative that began in response to recent racial incidents in Charlottesville; the initiative’s goal is to attract Black visitors and support Black businesses. While Jefferson’s life and notable accomplishments still remain at the forefront, new perspectives on the lives of enslaved people are being presented in richer detail. A recreated South Wing features The Life of Sally Hemings exhibit and new exhibits from the Getting Word Oral History Project, both of which opened in 2018, as well as the Post-1809 Kitchen exhibit, which opened in 2006.

“Historic sites play an essential role in influencing how people understand the past in a unique way,” says Brandon Dillard, manager of Historic Interpretation at Monticello. He adds that, during the late 1990s, “the field of public history began embracing marginalized narratives, and Black histories were being foregrounded in public discourse at a lot of historic sites that previously failed to include them.” Starting in 2000, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, the organization that owns Monticello, began requiring guides to incorporate the history of Sally Hemings and her children on all tours.

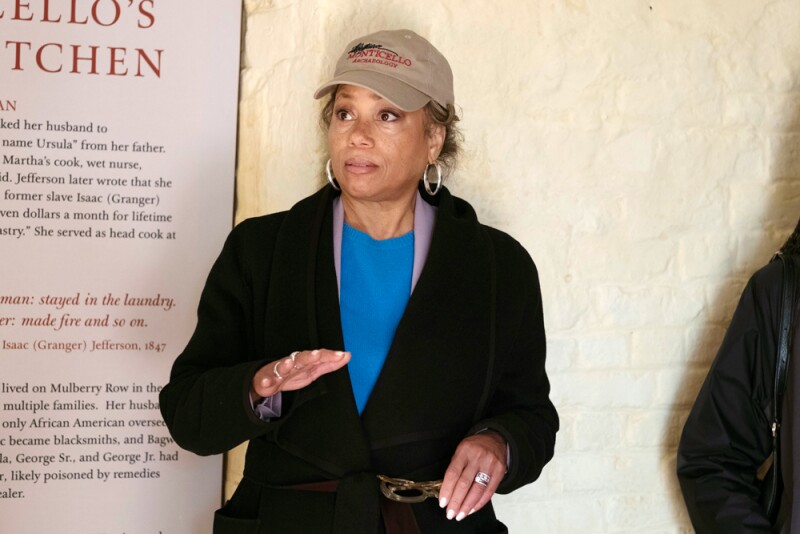

Gayle Jessup White, a descendent of Hemings, gives a talk at Monticello.

Photo by Justin Ide

Gayle Jessup White, a Hemings descendant and author of Reclamation: Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and a Descendant’s Search for Her Family’s Lasting Legacy, discussed the post-1809 kitchen in the Netflix series, High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America. In addition to the post-1809 kitchen, one of the places where White has felt a strong connection is the Granger/Hemings kitchen, Monticello’s first kitchen.

Only recently excavated in 2017, it’s where White’s great-great-great grandfather, Peter Hemings, learned the art of French cooking from his brother James Hemings, an accomplished chef who received culinary training while living with Jefferson in Paris. As part of his negotiation with Jefferson, James was granted freedom for teaching Peter his knowledge of cooking. White believes that stories like these demonstrate how much enslaved people had to maneuver and manipulate their circumstances to create lives of purpose.

White also recounted a story I knew nothing about when I first visited Monticello. One of the grueling duties performed by enslaved children was creating the red bricks used on the exterior of Monticello, and small imprints embedded in the surface of the bricks are easily visible when standing next to the home. White says, “Two hundred years later, we still see the marks of those children on one of the most recognizable structures in the world,” a building that graces the back of the U.S. nickel. Dillard suggests that white brickmakers employed by Jefferson likely used enslaved children to mold and form bricks, a laborious process typically performed by hand with clay and fire.

The momentous effort to move away from telling one version of history and provide honest, inclusive narratives about Jefferson and the people living and working at Monticello has brought stories from the shadows that have never been shared previously. White believes that Monticello has done an exemplary job at telling complete stories that humanize people who have been dehumanized. She considers Monticello her ancestral home and wants visitors to understand that enslaved people saw Monticello as their home, too.

Every tour at Monticello now includes histories of enslaved people, from the standard guided Highlights Tour to the more in-depth Behind the Scenes Tour. Dillard believes these tours lead visitors to consider the ongoing legacies of race-based slavery that American society still struggles with today. Dillard also believes that Sally Hemings’s life and history can be a lens through which we all can better understand slavery and the resilience of enslaved people and their descendants.

Though my second visit to Monticello didn’t change my view of Jefferson, it did provide a more accurate representation of what life was like from the perspectives of enslaved people on one of the best-documented plantations in the United States. And the inclusion of such diverse perspectives allows us to preserve, understand, and honor the histories and contributions of underrepresented groups to the world.