The move to retire abroad—whether full-time or even just for part of the year—is no light undertaking. After all, there are many things you don’t learn about a place and its inhabitants, bureaucratic woes, and myriad other idiosyncrasies until you’ve actually spent time living a daily life there.

We talked to five people from across the United States who opted to retire abroad—in Portugal, Japan, Morocco, French Polynesia, and Mexico—and they shared details about their living expenses and the unexpected joys and hurdles of choosing a different path.

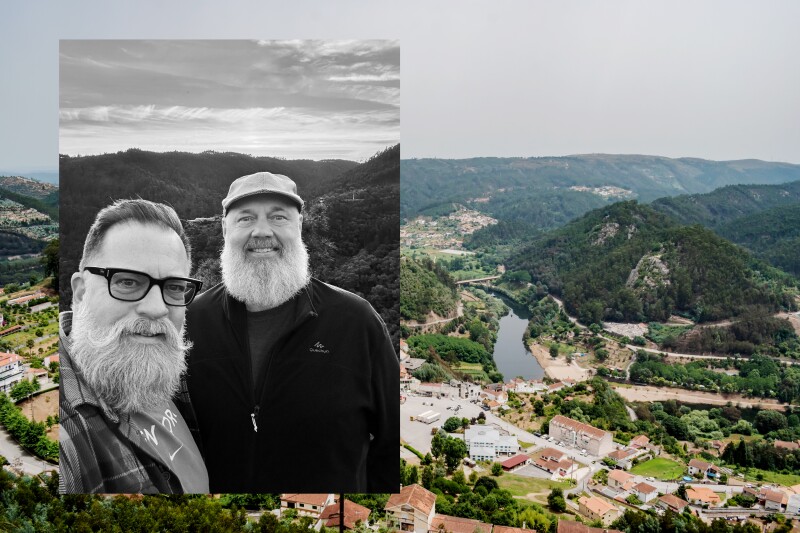

Bill Mauro, left, and Marcus Laurence moved to Portugal in 2019 and chronicle their adventures on Instagram; they also run a guesthouse.

Photo by Liliana Marmelo/Shutterstock; portrait courtesy of Bill Mauro

Bill Mauro, Portugal

Bill Mauro, 61, and his husband, Marcus Laurence, moved from Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, to retire in Portugal in 2019, starting in Lisbon and eventually settling just south of Coimbra, the country’s fourth-largest city and home to its oldest university. For the past 3.5 years, they’ve been living in a 130-year-old stone house they bought and renovated, sharing their adventures on Instagram.

What I pay for living expenses: We own our house and car outright. But our monthly expenses for everything else—including all insurances, groceries, utilities, dining out, and entertainment—comes to about US$2,300 per month.

Sample expenditure: A meia de leite (espresso with milk) in our village costs 1.20 euros to 1.50 euros (less than US$2)

What are the major pros or cons you’ve found living in Portugal? When it comes to finances, property tax is very low here, and we pay about 15 percent of what private health insurance costs in the U.S. The pace of life is slower, many people speak English, and there are beautiful beaches and Medieval villages, as well as tons of culture and history to explore.

Among the cons, learning Portuguese has been challenging and gas is expensive.

Any unexpected hurdles? Purchasing our home in the mountains was a challenge. It included seven small parcels of land that were not properly registered by the previous owner. Because of that, it took two years to sort out the paperwork and receive our deed.

What about unexpected joys? We have found the Portuguese people to be very helpful and welcoming. Also, the health care has been top notch. Marcus spent 12 days in a public hospital for complications related to AFib [atrial fibrillation, a type of irregular heartbeat] and it was 100 percent covered by the National Health Service.

Kurt Bell traded the urban grit of L.A. for the nature-surrounded setting of Shizuoka, Japan.

Photo by korinnna/Shutterstock; portrait courtesy of Kurt Bell

Kurt Bell, Japan

Kurt Bell, 61, left Los Angeles in 2014 and is currently retired and living near Mount Fuji in Shizuoka, Japan, the city his wife of 38 years, Yumiko, is from. Shizuoka, between Tokyo and Nagoya, is known for its surrounding rural and agricultural areas that grow tea and wasabi plants.

What I pay for living expenses: Our overall living expenses in Shizuoka are approximately 50 to 60 percent lower than what we were spending in Los Angeles. That difference comes from several factors: Groceries are cheaper, healthcare costs are dramatically lower, utilities are more modest, and we own our home outright—no mortgage or rent. Daily life here tends to be leaner, quieter, and less consumption-driven. Housing is about a third of what we paid in California, and health care is so dramatically less expensive it’s almost hard to compare. For example, in the U.S. I was paying around $1,400 a month for family health insurance. Here in Japan, for just my wife and me (our daughter is now grown and on her own), we pay about $170 a month total—that includes medical, dental, and prescriptions. It’s pretty amazing.

Sample expenditure: A latte at a good café where I live typically runs around ¥400–¥500 (roughly US$3–$3.50).

What are the major pros or cons you’ve found living in Japan? Shizuoka offers a quieter, more deliberate pace of life [than Los Angeles]. It’s nestled between sea and mountains, and the streets are clean, the trains run on time and there’s a deep cultural value placed on order, respect, and community. That suits our temperament quite well. Coming from L.A., though, the shift can feel stark at times. The variety and spontaneity of the city—the creative friction, the diverse food, the social energy—aren’t easy to replicate here. And of course, language remains a barrier, even after years of study and immersion. I find that some things just take longer, both logistically and interpersonally.

Moving here meant starting from scratch in many ways—not just learning systems, but letting go of habits and roles that made sense in America.

Any unexpected hurdles? I didn’t expect how much I’d have to recalibrate my sense of identity. Moving here meant starting from scratch in many ways—not just learning systems, but letting go of habits and roles that made sense in America. And while Japan is incredibly welcoming, it does require effort and humility to navigate life as a permanent outsider. Even seemingly simple tasks can require a surprising amount of patience and quiet adaptation.

What about unexpected joys? What’s been most surprising is how fulfilling a slower life can be. I walk three times a day. I eat lunch with my wife every afternoon. I tend a small garden. These small routines have become quiet rituals that anchor my days. There’s an elegance to life here that encourages presence over productivity. Retiring in Japan hasn’t just been a change in location—it’s been a change in rhythm and values.

Patricia Rachidi says that the best thing about living in Morocco is the people: “They respect their elders; there are no nursing homes here.”

Photo by SerFF79/Shutterstock; portrait courtesy of Patricia Rachidi

Patricia Rachidi, Morocco

Thirty years ago, after retiring from a career in jewelry manufacturing, Patricia Rachidi (now 84) made the move from Minnesota to Rabat, Morocco, where her husband was from.

What I pay for living expenses: I have a three-story house next to the beach in Morocco’s capital, Rabat. My property tax is $125 a year. My internet and telephone come to $32 a month. I have over 500 free channels, YouTube, Netflix, the works, which all runs on my Wi-Fi. I pay around $30 a month for water and electricity. I don’t need house insurance and don’t pay for garbage pickup. I have a driver, housekeeper, and gardener [for $300 a month].

Sample expenditure: A baguette at the bakery costs about 60 cents.

What are the major pros or cons you’ve found living in Morocco? Making friends is easy. Americans are very welcome here and, best of all, you can retire here very comfortably [if you have] a moderate, guaranteed income. But if you are not retired and you need to work, it’s not a good idea because wages are very low.

What about unexpected joys? Our forests are beautiful and clean and so are our roadways. But the best thing I’ve experienced here are the people. They are friendly, warm, and helpful. They respect their elders, there are no nursing homes here, and the children are polite and well-disciplined in most families.

It’s very joyous to know that two senior Americans could rise to the never-ending challenges of atoll life.

It was a 40-year dream of Carol Fuller to live in Tahiti. She even wrote a book about her move.

Photo by Danita Delimont/Shutterstock; portrait courtesy of Carol Fuller

Carol Fuller, French Polynesia

Originally from Southern California, Carol Fuller, 76, says she got “infected with the Tahiti disease,” from her parents, who loved the islands. She’s been regularly traveling to French Polynesia since 1985. Now she and her husband, Scooter, spend six months of the year on the atoll of Rangiroa in the Tuamotu Archipelago and the other six months at their home in Kona, Hawai‘i. She’s written a memoir about her experiences: Sand, Sea, and Sky: My Love Affair with Tahiti (Mascot Books, 2024).

What I pay for living expenses: My husband rides a Harley; I’m a surfer. We like the simple pleasures in life so we live simply. The cost of everyday items in Rangiroa, such as food, gas, and basic household supplies, is fairly comparable to prices in Hawai‘i. A trip to the store for basics on the atoll (food, beverages, and toiletries) is usually about $80. Lunch at a small local-style café with grilled fish and veggies can cost $35 per person. Our electricity bill there is also about the same as what we pay in Hawai‘i. Where you really see high prices is someplace like a hardware store, where simple items like spray paint, lumber, and WD-40 are exorbitant. We usually spend about $80 a day on daily living when we’re in Rangiroa, give or take.

Sample expenditure: $4 for a can of Coke in Rangiroa, $25 for a six-pack of the local Hinano beer.

What are the major pros or cons you’ve found living in Rangiroa? It’s incredible experiencing never-ending beauty on a daily basis and meeting other people who also live the atoll life. It brings everyone closer; we learn from each other and help each other. The Polynesian people are amazing. I started learning to speak Tahitian in 1985 and it has greatly helped us assimilate. My husband is a professional fisherman and his skills fit in perfectly here. Among the cons of living on a remote atoll, there’s a lack of availability when it comes to fresh food and everyday products, as well as medical services. Also, we can get by in French, but not being more fluent means we miss out on so much at social gatherings. I can say anything I need to in Tahitian and cobble things together with a combo of French and Tahitian, but I still get stuck sometimes.

Any unexpected hurdles? When you live in an atoll environment, everything depends on the weather. That includes everything from doing a load of laundry, since we line-dry things there, to flight schedules when you’re waiting for medicine or an urgently needed car or boat part to arrive. The weather is so much more unpredictable on an atoll—and its consequences are more severe. Our house is on the lagoon and is open wide all day to the elements, so we had to learn about the different winds and take note to protect our boat, house, and ourselves.

What about unexpected joys? Living in Tahiti was a childhood dream of mine that took 40 years to realize. It’s very joyous to know that two senior Americans could rise to the never-ending challenges of atoll life. Not many Americans attempt this, let alone two seniors. Life expectancy in the atolls is short because it’s a hard life. In our 70s now, we’re considered ancient. Having our own fishing boat and learning to fish alongside my husband, a seasoned charter captain in Kona, has been another joy. We’ve spent many days here on our boat just loving life.

Lucinda Young, standing, is active in her retirement: she’s on the board of a community arts organization and volunteers with an equine therapy program.

Photo by Mardoz/Shutterstock; portrait courtesy of Lucinda Young

Lucinda Young, Mexico

Lucinda Young, 72, and her wife, Shirley, moved from Santa Fe, New Mexico, to Merida, Mexico, for their retirement in 2012, before relocating to San Miguel de Allende in 2022. They chose Mexico for its proximity to family still in the U.S., its affordability, and its cultural offerings.

What I pay for living expenses: Even living in San Miguel, which is probably one of the most expensive places to retire in Mexico, our expenses are 20 to 30 percent less expensive than anywhere we’d actually want to live in the U.S. In San Miguel, you can buy a very nice house for around $450,000. In any of the attractive and Democratic Eastern Seaboard states, I don’t think you could buy a house of comparable design or amenities for close to that.

Sample expenditure: A half liter [17 fluid ounces] of milk costs between $1.50 and $3, a glass of wine in a restaurant is between $4 to $10, and you can get a decent bottle of wine for about $12.

Even living in San Miguel, which is probably one of the most expensive places to retire in Mexico, our expenses are 20 to 30 percent less expensive than anywhere we’d actually want to live in the U.S.

What are the major pros or cons you’ve found living in Mexico? Dealing with the Mexican banking system is tedious. Because of attempted protections against money laundering, among other things, Mexican banking is incredibly bureaucratic. For a relatively simple issue in the U.S. that you could go into a bank and see an operations manager for, you’d be in and out in 45 minutes. Here, that could take two days and two visits, each of which could take a couple of hours. The whole banking thing can be really a kind of big brain fry.

But the pros of living here far outweigh the cons.

Mexicans absolutely prioritize being in family—dropping off a bunch of flowers because it’s grandma’s birthday, taking an extra half hour for lunch because it’s a colleague’s wedding anniversary. Human relationships pervade every aspect of life here, and it’s just a constant source of delight.

The saints’ days are celebrated, the great days of history are celebrated, and they’re celebrated with this sort of enormous exuberance and deep investment that is somehow very, very touching, very embracing, and very inclusive.

Any unexpected hurdles? In many ways, Mexico is really very 21st-century in terms of technology. But anything that you have to do that deals with immigration, for example—something all expats have to deal with—or changing your driver’s license, renewing your driver’s license, needing to have your state or federal tax ID on some piece of paperwork because you’re going to buy a car or sell a car—anything like that is incredibly tedious and time-consuming.

What about unexpected joys? Mexicans have a way of waiting that is kind of beautiful, actually. They’ll sit and wait for a concert to begin or they’ll sit and wait for a procession to pass by. And they’ll sit with friends and family and they are never less than utterly at ease and engaged with each other. They never seem to be bored or frustrated or impatient. And that’s a great life lesson.

San Miguel has so much to do. There are a zillion NGOs that have been functioning here for many decades [with community programs and volunteer opportunities] that both Mexican nationals and expats participate in. There’s anything you could conceivably want to do or be interested in as a retiree. Whether you’re talking about volunteering or taking classes or learning horseback riding or taking tango lessons, it exists here in spades. I volunteer at an equine therapy program that’s a real mix of Mexicans and expats. So I get to do something that I love and care about that isn’t just totally an expat thing.