This story is part of Travel Tales, a series of life-changing adventures on afar.com. Read more stories of transformative trips on the Travel Tales home page—and be sure to subscribe to the podcast!

Outside, the September sun beat down on Lucca’s postcard streets with the ferocity of a boxer who knows his best days could be behind him. But inside, just a few months before the world went sideways, it was dark and cool and smelled of ink. Matteo Valesi put on some Bob Dylan and brushed clear a space at a table overladen with books and papers. He motioned for me to sit, then peered at me closely. “You’ll need to answer carefully,” he said. “This is not to be entered into lightly. I’ll need to know your family history, your passions, who you are.”

I wasn’t at this shop for therapy. I was there, at the Antica Tipografia Biagini, for a bookplate.

It had been decades since my previous visit. I was in college the first time I traveled to Tuscany, and my memories of that trip are mostly the standard-issue stuff of any backpacking student: the Leaning Tower of Pisa, the David, the sniffy waiters offended by dinner orders that consisted of a single plate of tortellini alla panna with a carafe of tap water, the hostels and gelato and trains and random Italian boys you make out with by the Ponte Vecchio. But there was one aspect of that trip that seemed a little more personal, something only a nerd like me could adore: the books.

As the birthplace of the poet Dante and a key center for scholarship during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Tuscany has long been associated with literature and the pursuit of knowledge. But because of its reputation for craft, it also preserves a relatively high number of enterprises devoted to books as objects: dusty, genteel bookshops lit by chandeliers; old-fashioned printshops; binderies that fashion book covers from irresistibly supple leather; libraries with their long tables and coy little lamps; students who come from all over to study book conservation.

And to me, nothing seemed a higher expression of that glorious book culture than the bookplates—those tiny, illustrated squares, also known as ex libris, that are pasted into volumes to identify their owners—which I discovered in a printshop window in Lucca.

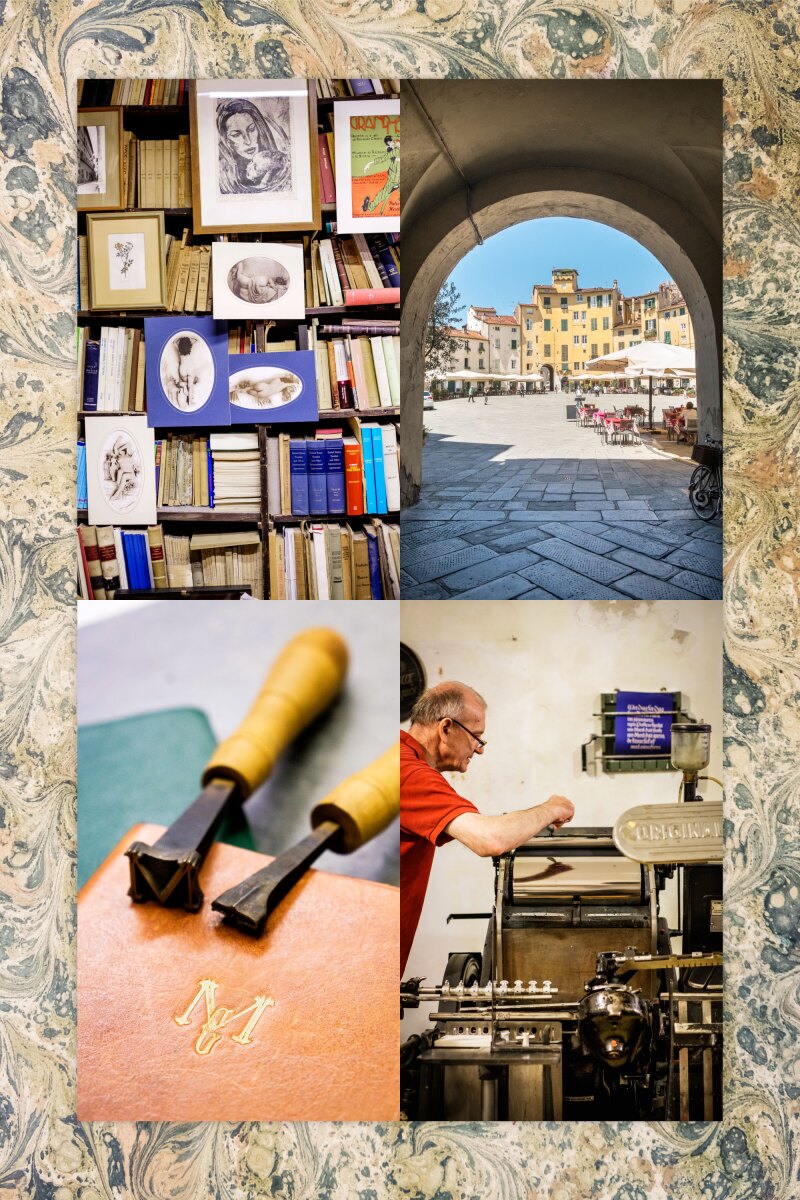

Clockwise from top left: Libreria Gozzini in Florence; Lucca’s Piazza dell’Anfiteatro; a Heidelberg press at Antica Tipografia Biagini in Lucca; a leatherbound book at Giulio Giannini e Figlio in Florence.

Photos by Francesco Lastrucci

I longed for one. Each was custom designed and hand printed, a small, exquisite work of art intended not merely to identify the owner, but also to express something about her, like the intellectual version of a heraldic shield. I entered the shop, and without a word, the ink-stained man inside looked up from his work, handed me a form, and sent me on my way.

Printed in an elegant font on thick paper was a series of questions. Favorite poet? Favorite time of day? Favorite number? Based on my answers, the printer would then design a bookplate just for me. Never, I thought in that moment, had I wanted something so badly. And yet I balked. It wasn’t the money, although I certainly didn’t have it. And it wasn’t that the questions were difficult, although some—favorite stone?—admittedly gave me pause. It was more that I could recognize, even in my callow state, my own callowness. A bookplate was a serious thing, I realized. It was a permanent sign of a person with tastes long cultivated. It was the kind of thing an aristocrat or an author with a shelf of books behind her might possess. I wanted to be a writer, but I certainly wasn’t one yet. I kept the form but never filled it out.

I never forgot about it, though, and after a couple of decades I began to wonder if I was ready. By then, I had established myself as a journalist and moved to Europe. I had even become an author, and if the shelf of my works was composed entirely of multiple copies of the one book I had published, at least I had a shelf. Finally, it felt like maybe I had earned my bookplate.

There was only one problem: By the time I was ready, books themselves were no longer what they used to be. Today, a book is not the thing that most of us turn to first for research, or to relax with at the end of the day. I googled Antica Tipografia Biagini to see if it still existed (it did), but could find no indication of whether it still designed those small squares of paper that attested to their owners’ love of books. And what of all the other bibliophilic enchantments—the binderies, the libraries, the book conservationists—I had encountered in Tuscany? Did they still exist?

The Ponte Vecchio, Florence’s iconic medieval bridge in the centro storico, is a short walk from some of the city’s best bookshops.

Photo by Francesco Lastrucci

I began my search in Florence. On my first day in town, I was relieved to find the Giulio Giannini e Figlio bookbindery exactly where I had left it, directly across from the Pitti Palace. I admired the letterpress cards and leather-bound notebooks, laid out just as seductively as before, as I headed to a cramped room in the back that looked like it hadn’t been tidied since the start of the Industrial Revolution. There, Maria Giannini was doing amazing things with a comb and a blow-dryer that had nothing to do with hair.

The sixth generation of Giannini bookbinders, Maria learned the craft from her father and her uncle. The latter still handles the actual binding, while Maria specializes in making the colorful marbleized paper that, in the Florentine style, is used to line the inside of book covers. She demonstrated the technique, drawing a comb across paint that seemed to float magically on the surface of the water, before placing the paper in the bin and allowing it to pick up mesmerizing, multicolored patterns. She then dried the paper with the help of that Conair 2000. “Marbleizing is relaxing,” she told me. “And sometimes it surprises me: the power of the colors and patterns that come out.”

As she worked, Maria told stories: Her great-great-grandfather made notebooks for members of Queen Victoria’s court, and Dostoyevsky once lived in the flat upstairs. But she spends the majority of her time looking forward rather than back at the past. Many of Florence’s other bookbinderies have closed, and she is desperate to avoid that fate. To supplement the notebooks and paper boxes that tourists buy, Maria offers classes. It’s not enough, though, and the question of how to survive keeps her awake at night. “I want to save the handcraft part of what we do. It’s even more important now, because everything is the same everywhere. So I have to find a way.” She turned to the wooden cabinets that line the workshop, opened a narrow drawer, and pulled out a tiny block. I peered at it closely and could make out the letter M. It was an ancient stamp used to decorate leather. “I’m thinking of making jewelry from them.”

Maria isn’t the only one trying to come up with new ways to survive. Many of Florence’s independent bookshops have closed, plowed over by giants like Rizzoli Bookstore and, of course, Amazon. Todo Modo, its shelves full of contemporary fiction and an alluring selection of graphic novels, was humming with life on the afternoon I visited, but only, a clerk told me, because of the author’s reading that was about to start in the event space toward the back. Across the street, at Art + Libri, Alessio Lupi told me the pleasantly jumbled shop was barely hanging on. Stocking nothing but art history books, it’s been an important resource in this art-centric city. “A specialized bookstore like this used to be the first place you’d turn if you were searching for something,” Lupi said. “Now it’s the last resort.”

Clockwise from top: The view from Siena’s Torre del Mangia; at Sator Print in Siena, Bertolozzi Caredio Piergiorgio uses a tool to open the binding of a music book, before beginning restoration; handmade notebooks at Giulio Giannini e Figlio in Florence.

Photos by Francesco Lastrucci

But perhaps nowhere was that sense of holding out stronger than at Libreria Antiquaria Gozzini, a shop for rare books that has been a Florentine fixture for more than a century and a half. It took me a while to find it, because its location across from the Galleria dell’Accademia Firenze meant the storefront was obscured by the massive crowds waiting to get in to see Michelangelo’s David. “You’d think it would be great to have so many people passing by,” lamented Edoardo Chellini, the store’s co-owner, once I had pushed my way into the shop. “But it’s like a wall. No one can get through.”

Gozzini got its start in the mid-19th century, when Oreste Gozzini began selling books in the square outside the Duomo. About 170 years later, his great-great-great-grandson showed me around the warren of overflowing rooms, one capped with a Murano chandelier. “Some people come in for the smell alone,” Chellini said. Though just 29, he had a pre–Internet Age reverence for the printed page that emanated from him as he showed me some of his treasures: excerpts from a 16th-century text produced in the early days of the printing press, a set of erotica from the Victorian era, the shop’s hand-typed card catalogue. “Why do books matter?” he said. “Because history matters. Books are our memory.” I thought of objecting that the history contained in them is still available in digital form. But there, with the scent of old paper wafting from the handsome shelves, I knew what he meant: Held over their life spans by who knows how many other pairs of hands, books are history you can touch.

As if on cue, a white-haired man in a tweed jacket entered from the street. “Buon giorno, professore,” Edoardo greeted him. Many of Gozzini’s customers these days are older, and Edoardo worries about the future of the shop. “I really want to keep this going, not just for me and my family, but for the city,” he said. “It’s part of Florence’s history.” Every day, he considers ways to get the people to come in. “Maybe we give tours,” he said with a shrug. “Or maybe we’ll open a café in the garden.”

It seemed a peculiarly Dantesque form of purgatory, to be faced day in and day out with the legions who could save your family business if only they’d notice you, and it put me in a melancholy frame of mind as I headed to the Laurentian Medici Library. Tour groups clustered in the patio there too, but when I climbed Michelangelo’s staircase, with its gentle, puddle-like curves, to the library upstairs, I found it virtually empty. Sunlight streamed through the stained glass windows and illuminated the lists of titles scrawled down the side of each of the pews, which had been designed in the early part of the 16th century by the artist and writer Vasari—the first person to use the word rinascita, or rebirth, in print. “That’s not graffiti,” whispered the docent, Gianluca Ciano. “It’s the catalogue—it tells you what books were kept on this row. Here, you came to the books, instead of the books coming to you.”

The tomes were transferred long ago to another library, but the thin metal chains that protected them from avaricious scholars were still there. “If they didn’t chain them down, people would steal them,” Ciano added. “Back then, books were more valuable than gold.”

That comparison came back to me the next day, when I visited another library, the Marucelliana, where simply locating the reading room felt like finding buried treasure. It’s open to the public, but when I arrived late one afternoon, there was no one there save for an attendant. She informed me that the reading room was closed, but a little begging on my part convinced her to dial someone who, after a few minutes’ negotiation, granted me permission. “We’ll have to be quick,” she said. “So stay close.”

With that, we plunged into the stacks. We took a right past Moral Philosophy, a left by the biographies of the Italian patriot Garibaldi, then right again before riding an elevator to more stacks and winding our way through them as well. Finally, my guide pushed open a door, and I gasped. We were in the reading room—half inner sanctum, half Hogwarts—, where the dark, ornate cases that filled every inch of wall space were lined with books, and the long, polished desks spoke of centuries of scholars hunched over pages. I could have stayed for hours, but my version of Dante’s guide, Virgil, pushed me along. We paused only to admire a bust of the guy who founded the place in 1752 as a library for the poor, an exception to most libraries at the time, which were reserved for the elite. And then, before I could process it all, I was herded back into the elevator, through the maze, and out into the street.

It was thrilling to find these places—Giannini, Gozzini, Marucelliana—shrines to a time when books mattered. But they also made me acutely aware of how past that time is. Nostalgia wafted from them as steadily as the scent of old leather and paper, and it wasn’t hard to imagine a day when they too would surrender to time and technology.

Michiko Kuwata, co-owner of AtelierGK Firenze in Florence, prepares a Latin- Italian dictionary for restoration.

Photo by Francesco Lastrucci

But Tuscany’s culture of books looks forward as well. Michiko Kuwata, a Tokyo native, moved to Florence to study painting and book conservation, but 18 years later, she and her partner, Lapo Giannini—of those Gianninis—are working to reinvigorate the ancient crafts from their tiny studio in the Oltrarno quarter south of the Arno River. Kuwata still restores books, using tools—a tiny pair of fine-edge scissors, a collection of plush brushes—nearly as beautiful as the volumes she conserves. On a single book, it takes her two full weeks of 12-hour days to reverse the affronts of age and overeager readers. She has an intimate connection to the past, but she doesn’t worship it. She held out a heavy, embossed book she was working on. “It’s nice, but it’s very . . .” She paused before settling on the proper adjective. “Old.”

At the bench next to her, Lapo nodded in agreement as he heated a tiny awl and used it to melt silver leaf. “Tradition here can be oppressive,” he said. Eager to do more modern work, he and Michiko opened AtelierGK Firenze in 2010. “Tourists just want the heavy Renaissance binding or the marbled paper,” Lapo added. “We’re trapped by the imaginary idea of Florence.”

Michiko and Lapo have fought their way out of that trap with their contemporary takes on hand-decorated paste paper and buttery leather books, especially by pursuing their true passion: to handcraft one-of-a-kind books that are works of art in their own right. They showed me a four-volume set evoking the seasons. Winter stood out, its luscious turquoise cover inlaid with a pane of blue glass atop rippled paper.

In a working-class neighborhood a few kilometers up the Arno, Piccola Farmacia Letteraria is also bringing new life to the old neighborhood bookshop. Elena Molini opened it in 2018, when she tired of the big-box approach to selling books and went looking for a more intimate connection with her readers. The solution? To treat books as the medicine they are. Working with a team of psychologists, Elena put together the shop’s selection of 6,000 books, then categorized them by emotional state: Anger, Love, Loneliness. “Most of them are contemporary novels, not self-help books,” she says. “Narrative is more universal, because it puts characters first. And if you identify with a character, it can open your mind to how you might respond in the same situation.” I ask her what she would prescribe for bibliophilia, and she thinks for a minute before reaching for a copy of The Pocket Guide for Book Maniacs, a volume that tracks the best novels sold by Italy’s best bookshops.

As I left Florence and traveled across Tuscany, I kept coming across much of the same—a handful of bibliophiles, intent on keeping the old book arts alive. In Siena, Bertolozzi Caredio Piergiorgio showed me an 18th-century volume he was restoring after its present owner’s preschooler had used a Bic pen to supplement its illustrations of animals. But restoration is only part of what he does at his shop, Sator Print. In addition to binding books, he taught himself calligraphy and manuscript illumination. With his quiet, meticulous presence and the paper clip holding his glasses together, he reminded me of a medieval monk, except that many of his commissions these days come from Jewish tourists who request his skills for the prayer books used at Passover seders or the ornate wedding contracts called ketubahs.

On the other side of Siena’s striped cathedral, I found Duccio D’Aniello shooing away tourists who had stopped to eat pizza on the ledge of his shop window, blocking the view of the antique volumes and prints he sells inside. Itinera di Duccio D’Aniello dates back only to 1984, but his parents have run a famous rare bookshop in Rome for longer than that, and the shoebox of a space is stuffed with such marvels as a 16th-century herbolarium and an illustrated guide to Tuscan ornithology. “There aren’t many collectors left,” he said, so he survives on the tourists—presumably not the same ones who would plop down for a slice on his stoop—who come looking for what he described as “a nice, original souvenir.”

Finally, I reached Lucca and made my way to Antica Tipografia Biagini. The place was just as I remembered it, though its owner had changed. Matteo Valesi was visiting his family in Lucca in 2008 when he stumbled across the printshop and immediately fell in love. Its founder, Gino Biagini, could handle the famously finicky Heidelberg Class 1951 press the way Michael Schumacher can handle a Ferrari, and his talent had earned him an international clientele. He had designed ex libris for Jodie Foster and Robert De Niro. But Gino was by then exhausted from the work and the 60 cigarettes he smoked a day, and Matteo, though he had no experience as a printer, convinced him to pass the shop along to him.

Now, Matteo pulled out scrapbooks and showed me examples of the shop’s work. Page after page was filled with gorgeous squares, each one somehow representative of the book lover who had commissioned it. One plate had the book owner’s name printed in block letters on the body of a 1920s propeller plane; another bore a cozy scene of a library with a quote from Lord Byron. In one of my favorites, a single finger from an outstretched hand drew ripples in water embossed with the Latin phrase Primum facere, deinde philosophari—First do, then philosophize. “So you see,” Matteo concluded, “an ex libris is not something you choose on a whim. It is with you forever.”

“A sign of identity,” I said. “Like a tattoo.”

“Ecco!” he cried, and for a moment I thought he was going to hug me. Instead, he slid across the table a blank, identical copy of the form I had picked up all those years before. This time, I reached for a pen.

>>Next: A Bibliophile’s Guide to Tuscany